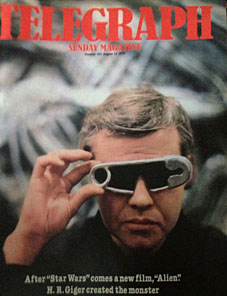

HR Giger. Photo by Eve Arnold, 1979.

The news of HR Giger’s death was prominently featured in UK papers, something that wouldn’t have happened without his connection to the Alien films. Artists like Giger seldom make the front-page news even though he was well-established before the call from Ridley Scott. He’d already worked on Jodorowsky’s aborted Dune project alongside Moebius (who also did some work on Alien; people forget that), and his work had even appeared in a major feature film before Alien with a blink-and-you-miss-it appearance from his portrait of Li Tobler in Alain Resnais’s Providence (1977). Alien may have made him world-famous but I’ve always felt that Ridley Scott needed Giger far more than Giger needed either Scott or Hollywood. Paul Scanlon and Michael Gross’s The Book of Alien (1979) shows the production designs for the alien components before Giger’s involvement, none of which had the requisite strangeness that made the film such a success. That success would have made many artists decamp to Los Angeles in the hope of repeating the trick but Giger kept his distance. You can’t blame him when his work was diluted by James Cameron in Aliens while a unique project like Clair Noto’s The Tourist—which had heavy Giger involvement—never got made. (See here and here.)

The following is the first interview I read with Giger, a feature in the Sunday Telegraph magazine from August 1979, shortly before Alien was released in the UK. I wasn’t sure whether I still had this since I’d chopped up some of the other pages in the 1980s when I was making collages. The Sunday Telegraph then was even more of a stuffily conservative title than it is now so it’s a surprise to see Giger given such treatment; he was also the cover star although the cover on my copy is lost. I was given this by a friend whose parents read the paper; the only time I’ve ever bought the Sunday Telegraph was when I appeared in it in the early 1990s for a piece about Savoy Books. The interviewer on that occasion was Byron Rogers who I’m surprised to find wrote one of the other pieces in this magazine. (Thanks to Joe for sending me a picture of the missing cover!)

* * *

THE MAN WHO PAINTS MONSTERS IN THE NIGHT by Robin Stringer

The man in black is talking about his monster. “It is elegant, fast and terrible. It exists to destroy—and destroys to exist. Once seen it will never be forgotten. It will remain with people who have seen it, perhaps in their dreams or nightmares, for a long, long time. Perhaps for all time.”

The man in black is talking about his monster. “It is elegant, fast and terrible. It exists to destroy—and destroys to exist. Once seen it will never be forgotten. It will remain with people who have seen it, perhaps in their dreams or nightmares, for a long, long time. Perhaps for all time.”

The speaker is H. R. Giger, a Swiss-German surrealist painter, who designed the monster for Alien, the latest screen shocker, made in British studios under British direction to meet the apparently insatiable twin public cravings for space and horror films. Alien has already persuaded Americans to queue in record-breaking numbers outside their cinemas. It is said to have recouped its £15 million cost within 26 days of opening, and it comes to Britain on September 6.

The crew of a space tug on a fuelfinding mission answer a distress signal from an unknown planet. They land and discover an alien spacecraft in which, unknown to them, an awful creature has been spawned and waits seething, but with infinite patience, for a chance of life. Taken on board the space tug, clinging to one of the crew, the creature parasitically reproduces itself in him and bursts out into life in a welter of blood. It proceeds to make itself at home on board by hiding in dark places and jumping out at passers-by. It gobbles up the space crew one by one and grows prodigiously. Being unfamiliar with the monster’s lifestyle, the crew understandably panic.

That in brief the story of Alien, which, of course, has actually been spawned by the movie makers to scare us just a little bit and, in the process. to make them a lot of money.

The man who designed the monster will make some money, too—though not a lot, he says. He is not on a percentage. H. R. Giger, who calls himself H.R., because “the other things are too long and complicated”, is a chunky 39-year-old who lives with his girlfriend/secretary Mia, two cats, 12 skeletons and some books on magic in the middle of a rickety row of terraced houses in the industrial outskirts of Zurich. He always wears black.

There, with airbrush, he paints his weird nightmarish paintings which blend the human form (usually a highly stylised naked woman) with machinery, reptiliana and bones. The pictures are often extensions of his nightmares.

Giger, on the other hand, is friendly, chatty and down to earth. “We mostly work at night,” he says, “so we have no ‘phone calls. I work while Mia reads to me from different books—from Dune, from Old Magicians, or from the novels of Gustav Meyrink, the romantic mystic who died in 1932. We work till three or four in the morning and sleep in late.

“I work in the way of the Surrealists. I sit before a white canvas and begin with an airbrush. I don’t know what will happen. I am curious to know. I often surprise myself.”

To those who complain that his paintings are frightening, ugly and emotionally cold, he replies: “People say many things about my pictures because they are unusual. I don’t like ugly things. I think my creatures are beautiful in another way. You measure everything by the human being. If you know them a little, you think differently. It’s always the new things you are frightened of.

“It’s also that I want to find out what’s in my body. It’s like an analysis, like going to a psychologist. It’s how you find out what you are occupied with what obsesses you. It’s a purifying process.

“As for warmth, visitors who come to our house never find it cold. There’s a harmony here.”

Eve Arnold, the photographer who visited Giger, vouched for the warmth of the welcome. “After the first day’s work between the witches and the skeletons, not to mention the black ceilings and the mind-provoking art, I was rather afraid I would have nightmares.

“Not so: it was all so friendly and pleasant that I began to enjoy my strange surroundings, to relish pizza by candlelit skulls and to appreciate my gentle hosts. The dining room housed a magnificent black table designed by Giger and a sculptured automaton, in the bowels of which were a large brass platter bearing some decaying apples (real) and a black cat (live). On the table there were black candles in a surreal candlestick also made by Giger. The ceiling was black and there were no windows. They had been boarded over, with huge murals which were everywhere in the tiny house.

“In the studio there were 12 skeletons. In addition to the real ones there was a lovely one in metal. There is a witches circle there, too, where the house witch lives. Mia, who was wearing a black & apron with a white skeleton painted on it, giggled and said they should try to enlist the witch’s help to get the people next door to move. Then they could buy the house and join the two together to give them more room.”

Giger plainly values his present relationship with Mia. “She works as my secretary and we work very close. We each need the other. I am very happy to have found Mia. This time it’s going much better with my mental state.” The couple have no children. “We have two cats, one Siamese and one black. They are like our children,” says Giger. “I want very much to keep my freedom and you have to care about children so much.”

Mia interrupts again. “He cares so much that he is very afraid to have a child. He thinks about the world.” “Maybe later,” rejoins Giger.

Giger has not always been as happy in himself and his relationships. His nine-year love for Li, an actress, ended on Whit Monday 1975 when she shot herself with a revolver. The misery of his school days and of his military service still haunts him. “I sometimes have bad dreams: mostly the same dreams and they are about military service and school. 1 cannot kill them. I don’t know how to kill them, so that they do not come again.”

He has written about all these events and recorded other influential experiences, particularly from his childhood, in a book called Necronomicon, published in 1977.

His father was the proprietor of a pharmacy at Chur which he vainly hoped his son would eventually take over. Though young Giger had a sister, she was six years his senior and only played with him when ordered to. He grew up as an only child with the pharmacy as his playground.

When a fair came to town he used to spend all his pocket money taking rides on the ghost train. One year when the fair left he was “stricken with a sense of loss so great that I decided to build a ghost train of my own in the corridor of our house which, because of its length and its many corners and recesses, was ideally suited for the purpose.

“I built human skeletons from cardboard, wire and plaster, and trained coloured lights on them with a pocket torch. My playmates were dressed in white sheets, or were hidden along the track operating mechanisms which raised the lid of a coffin, moved a hanged man slightly on a branch, or opened the jaws of a hideous monster.”

Giger ran the ghost train for years, improving it continually and charging his sometimes reluctant customers five centimes a trip. At about the same time, the young Giger came under the influence of his uncle, Otto Meier, a primitive painter who kept a smallholding and ran a guest-house. Meier introduced him to the art of working in wood and metal and of hunting with bow and arrow and gun.

Giger admits to having been equally bad at all subjects at school with subjects the exception of drawing, in which art he distinguished himself among his friends as an illustrator of fantasies. So at 18, when the time came to leave school, he went to work as an unpaid draughtsman for a firm of architects.

After military service, which he found “monstrously boring”, he joined a building business as a planner. He maintained his enthusiasm for life by drawing.

In 1962 he entered the School of Arts and Crafts in Zurich, emerging four years later with a diploma in interior and industrial design. By 1972 he was working with an airbrush and was able to live by his painting alone.

Now recognised as “successful” even by the Swiss, who at first had scorned him, he sees in his art a reaction against Swissness. Mia chimes in: “A lot of boring things make you aggressive. Just to see a little bit of dirt in this clean country becomes a compulsion.”

Giger’s participation in Alien as a designer of sets and costumes as well as the monster was brought about by the British director, Ridley Scott, after he had been shown examples of the artist’s work. Talking of the alien spacecraft Giger says: “They asked me to design something which could not have been made by human beings—which is quite difficult. I tried to build it up with organic-looking parts—tubes, pipes, bones, a kind of art nouveau. Everything I designed in the film used the idea of bones. I made the model of the alien landscape with real bones and put it together with plasticine, pipes and little bits of motors. I mixed up technical and organic things, which I call biomechanics.”

Giger spent over five months at Shepperton Studios working with a team of film designers which included three Oscar winners from Star Wars—John Mollo, costume designer, and art directors Roger Christian and Les Dilley.

He is quick to attack those who, confronted with his creations, react with horror, seeing them as the product of a madman. “People who say that think themselves healthier and in some ways better than me. But if they are really honest, as I try to be, they will be unable to deny that they, too, are often tortured by evil thoughts or pursued by terrible nightmares.

“I have often noticed mothers trying to hide my works from their children, yet these little monsters are without equal when it comes to torturing animals or their fellow human beings.”

Photographer Eve Arnold recalls that, at the London studio where Giger worked for five months on Alien, one of the film crew drew a funny picture of him in the men’s lavatory.

Under the Giger profile topped with a halo was the legend “Giger paints nice things in secret”. •

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Hans by Sibylle

• HR Giger album covers

• Giger’s Necronomicon

• Dan O’Bannon, 1946–2009

• Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune

• The monstrous tome