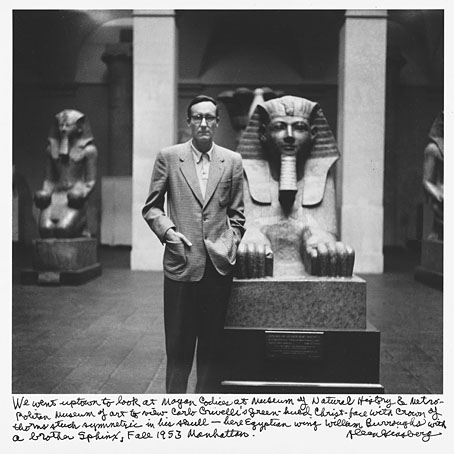

William Burroughs, New York, 1953. Photo by Allen Ginsberg.

Lonely lemur calls whispered in the walls of silent obsidian temples in a land of black lagoons, the ancient rotting kingdom of Jupiter – smelling the black berry smoke drifting through huge spiderwebs in ruined courtyards under eternal moonlight – ghost hands at the paneless windows weaving memories of blood and war in stone shapes – A host of dead warriors stand at petrified statues in vast charred black plains – Silent ebony eyes turned toward a horizon of always, waiting with a patience born of a million years, for the dawn that never rises – Thousands of voices muttered the beating of his heart – gurgling sounds from soaring lungs trailing the neon ghost writing – Lykin lay gasping in the embrace can only be reached through channels running to naked photographic process – molded by absent memory, by vibrating focus scalpel of the fishboy gently in a series of positions running delicious cold fingers “Stand here – Turn around – Bend”

The Ticket that Exploded (1962)

William Burroughs always talked favourably of Ernest Hemingway, and the famously spare style of Hemingway’s prose is evidently a style he sought himself, especially in the later works where there’s less of an emphasis on linguistic pyrotechnics. Something that always strikes me when I return to Burroughs’s earlier novels is the quality of passages like the one above which is a long way from the Hemingway style. What’s even more noticeable—and this is something which attracted me to Burroughs’s work from the outset—is the degree to which some of these passages are reminiscent of HP Lovecraft. In the case of the example above, taken from The Black Meat chapter of The Ticket that Exploded, some of this may be the work of Michael Portman who Burroughs credits as co-writer. What Portman contributed to The Black Meat and another chapter of that novel I’ve never discovered but there are plenty of other examples by Burroughs alone to show that he wasn’t incapable of this himself. The Ticket that Exploded was the first Burroughs book I read, and part of the shock and fascination came from encountering a recognisable Weird Tales-style atmosphere wrenched into inexplicable and thoroughly alien territory.

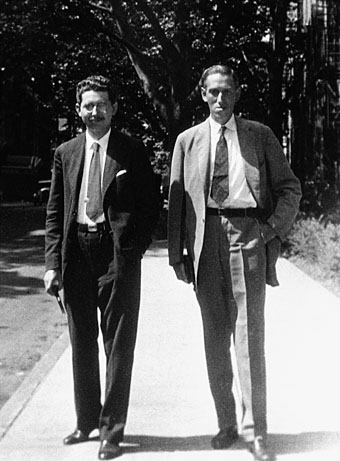

Frank Belknap Long and HP Lovecraft, New York, 1931. Photo by WB Talman.

There are others connections beyond literary style. When the Simon Necronomicon was published in 1977 Burroughs was asked to provide a blurb for the book. He wasn’t as effusive as the publishers might have hoped but the dubious volume was still advertised with his recommendation:

Let the secrets of the ages be revealed. The publication of the Necronomicon may well be a landmark in the liberation of the human spirit.

If it wasn’t for this then the extraordinary Invocation which opens Cities of the Red Night (1981) would have been diminished. Among the other “gods of dispersal and emptiness” whose names are called, Burroughs mentions “Kutulu, the Sleeping Serpent who cannot be summoned”, and “the Great Old One”, among a number of the usual Mayan gods, and several Sumerian deities whose descriptions (as with Kutulu) are taken from the pages of the Simon Necronomicon. It’s impossible to imagine Saul Bellow or John Updike opening a novel this way, just as it’s impossible to imagine many genre writers wandering into the areas that Burroughs explores elsewhere in that novel. This is one reason why Burroughs (and JG Ballard) were included in DM Mitchell’s The Starry Wisdom anthology in 1994, an attempt to expand the acceptable boundaries of Lovecraftian fiction, and also wilfully trample the fences that separate the genre and literary camps. I campaigned at the time for The Black Meat chapter to be included but Dave was set on Wind Die, You Die, We Die from Exterminator! (1973), a lesser piece although in the end it didn’t seem out of place in the book as a whole.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

• The William Burroughs archive

I always used to say, half in jest, that Lovecraft is like Burroughs minus the scissors and cocks. There were a lot of affinities between the two men: both were very lean and tallish, and both tended towards a habitual facial expression which was emotionally neutral while suggesting awkwardness and discomfort. Both were outsiders who dreamed of interdimensional voyages, and both adored cats while seeming often indifferent to human beings. The crucial difference was that Burroughs was as preoccupied by sex as Lovecraft appeared indifferent to it, and hence one was a Puritan and the other a radical apostate.

There’s another Lovecraft/Burroughs link, of course: Robert H. Barlow, HPL’s friend, correspondent, and literary executor, who in later life became head of the Anthropology department of Mexico City College and a scholar of Mayan texts and language.

Burroughs studied Mayan under him in 1950, and mentions his suicide the following year in a letter to Ginsberg. Barlow was apparently being blackmailed because he was gay.

There’s at least as much Clark Ashton Smith in that passage as there is HPL….

Tristan: I almost used photos of WSB and HPL with their cats then changed my mind when I found the Ginsberg pic. (The sphinx is still a cat, of course.)

Paul K: Thanks, I’m fairly sure I didn’t know about the Barlow connection otherwise I’d have mentioned it. I tend to horde these scraps of information.

The quoted passage is very Smithesque indeed, there’s even mention of “ichor” when it continues, a word CAS uses with great abandon in his more florid stories. If those sequences were drafted by Michael Portman he must have been reading pulp fiction of some sort. Burroughs makes direct reference to one of Henry Kuttner’s sf stories in The Soft Machine.