The pulp fiction of the early 20th century favoured remote or uncharted islands as locations for the bizarre and the fantastic; in isolated jungles all manner of savage and grotesque behaviour could take place out of sight of the civilised world. Islands are secure from interference; they can be visited by accident or intention, and later fled from when everything goes wrong. The Island of Doctor Moreau is an early example of the type although Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island (1874) pre-dates it by twenty-two years. The Island of Lost Souls (1932), the first film adaptation of the Wells novel, is one of a crop of mysterious islands that appeared in the 1930s following the success of the Universal adaptations of Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931). The recent Eureka DVD/Blu-ray edition of the film is the first UK release to present the film in its original, uncensored form. I watched it this weekend.

Moreau (Charles Laughton) and Montgomery (Arthur Hohl) at work.

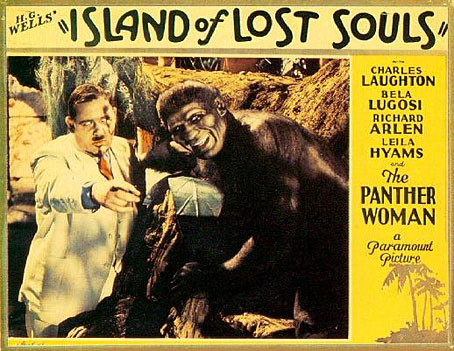

HG Wells famously hated the film, and his vociferous complaints helped to ensure it was banned in Britain until 1958. Even without Wells’ complaints there was enough there to bait the censors who declared it to be “against nature”: writers Philip Wylie and Waldemar Young push the erotic implications of Wells’ story to a degree that would have been impossible in 1896, and would be equally impossible two years later when the Hays Code clamped down on cinematic salaciousness. Charles Laughton’s Moreau is eager to discover whether Lota, the Panther Woman (Kathleen Burke), will show any sexual interest in the marooned Edward Parker (Richard Arlen). The bestiality theme continues when Parker’s fiancée arrives on the island and finds one of Moreau’s Beast People at her bedroom window. Add to this Moreau’s declaration that he feels like God (a similar line was cut from James Whale’s Frankenstein), a traditional British squeamishness towards maltreating animals (unless they’re foxes), and the Panther Woman’s skimpy outfit, and it’s no surprise that the authorities collapsed with the vapours.

Sensationalism aside, this is one of the greatest horror films of the early 1930s, and one which follows its source material with much more fidelity than Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein. The production had been commissioned by Paramount to capitalise on the success of the Universal films, hence the presence of a very hirsute Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law. Cinematographer Karl Struss had worked the year before on Rouben Mamoulian’s excellent Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; prior to this he photographed Sunrise (1927) for Friedrich Murnau. The combination of Struss’s chiaroscuro compositions, some adept direction from Erle C. Kenton (including crane shots), and a tremendous performance by Charles Laughton puts The Island of Lost Souls in a different league entirely to Tod Browning’s stagey and over-rated Dracula. Laughton’s cherub-faced Mephistopheles is a performance that runs counter to the cod theatricals of the period: he’s sly, confident and completely authoritative even if he looks nothing like Wells’ white-haired doctor.

Parker (Richard Arlen) and the Panther Woman (Kathleen Burke).

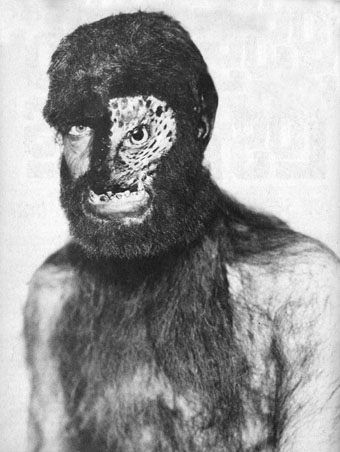

Moreau’s South Pacific island is one of those glorious studio-bound locations which we first encounter through a pall of mist. Despite its remoteness, the compound is a very Modernist affair, all white stone blocks and black iron bars with some Frankensteinian electrical equipment in the laboratory. The white stone embraced by jungle’s darkness reinforces the white/black symbolism and a colonial motif that runs through the film: all the principal human characters are white people in white clothes, while the Beast People are dark-skinned and clad in grey or black overalls; Moreau refers to them several times as “natives” despite them being his imported creations. The exceptions are the Sayer of the Law’s white shirt, and Lota’s bikini, the two characters most clearly situated between the human and animal worlds. The Beast People are mostly of the humans-with-animalesque-heads variety but there are glimpses of the kinds of hybrids Wells describes, including a very brief sighting of the remarkable creation below.

Without the censorship problems blighting its visibility there’s no doubt The Island of Lost Souls would have a greater reputation today. It’s not only the best adaptation of Wells’ novel, it’s also one of the first American horror films with a contemporary setting. That it also carries a wealth of subtext only adds to its attractions. Its release in December 1932 places it between two other notable island films.

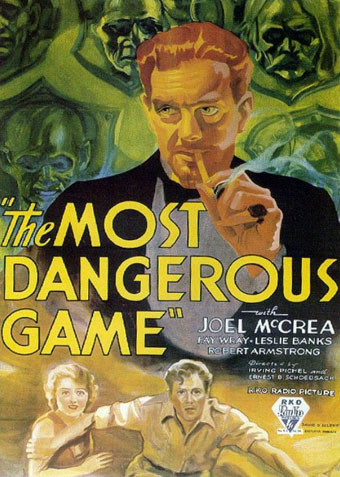

The Most Dangerous Game appeared a few months before The Island of Lost Souls. The film is well-known today for being a close cousin of King Kong (1933) with whom it shares writer James Ashmore Creelman, directors Irving Pichel & Ernest B. Schoedsack, actors Fay Wray, Robert Armstrong and Noble Johnson, and soundtrack composer Max Steiner. More importantly it also shares King Kong‘s Skull Island jungles, the films being shot side-by-side using the same sets. The screenplay is an adaptation of Richard Connell’s oft-anthologised short story about General Zaroff, a Cossack aristocrat and big-game hunter who enjoys hunting human beings on his Caribbean island.

The Most Dangerous Game: Zaroff’s fortress.

The film moves the island to the South Pacific, and also demotes the general to a count. Leslie Banks plays Zaroff, a man with a buffalo-scarred forehead and dubious accent. Joel McCrea’s Bob Rainsford is another big-game hunter who ends up on the island after a shipwreck. Zaroff’s “most dangerous game” is his punning description for his own sport and its human prey, “Outdoor chess!” as he puts it when challenging Rainsford to an unevenly-matched duel. Fay Wray’s Eve character is another under-developed female part added to a story which originally was male-only. As though in training for King Kong she’s dishevelled by the jungle and an alligator-infested swamp, and also required to scream a couple of times. The film originally ran over 70 minutes but preview audiences objected to an extended scene in Zaroff’s trophy room where the demise of his earlier victims was described in detail while Rainsford was being shown their stuffed corpses. The shortened version runs a mere 64 minutes, and all we see of the trophy room are some mounted heads, but it’s a taut thriller which I’ve often watched as a double-bill with the third film in this trilogy, King Kong.

The Most Dangerous Game, and a shot that could easily be mistaken for King Kong.

There’s little that needs to be said about King Kong but seeing as HG Wells is the ghost at this feast it’s perhaps worth noting that the idea of giant animals is one that Wells had already explored in his 1904 novel, The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth. There’s also an early story, Aepyornis Island (1894), with a sailor shipwrecked with a giant bird that should have been extinct for over 1000 years. Wells’ early fiction ran the gamut of fantastic themes so it’s no surprise to find a precursor for Kong. I’ve never seen a comment from Wells about the film but he was dismayingly literal when it came to cinema—he was scathing about Fritz Lang’s Metropolis—so would no doubt complain about the anachronistic dinosaurs. Two films based on his work that he did approve of, The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1936), and Things To Come (1936), aren’t bad but neither bear comparison with The Island of Lost Souls.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Doctor Moreau book covers

• The Island of Doctor Moreau

• Harry Willock book covers

• The Time Machine

• The Magic Shop by HG Wells

• HG Wells in Classics Illustrated

• The night that panicked America

• The Door in the Wall

• War of the Worlds book covers

In spite of what H. G. Wells thought, I love this film. Well, John, merry Christmas, happy New Year!