The Time Machine (1960).

The turning over of the calendar from one year to the next makes this day the ideal moment to write something about HG Wells’ celebrated story. Having re-read The Magic Shop before Christmas I decided to refresh my reading habit—lapsed these past months due to pressure of work—by revisiting more of Wells’ short stories, many of which I haven’t looked at for years.

As I said in that earlier post, it was The Time Machine that led me to Wells’ written work after being excited at an early age by George Pal’s 1960 film adaptation. Reading the story again I’m still astonished by how advanced it is compared to everything else being published in 1895. Michael Moorcock’s excellent introductory essay, The Time of ‘The Time Machine’ (1993), notes that time travel per se wasn’t a new idea for Victorian readers, there were many novels and stories using the theme, most of them merely displacing a character from one age to the next in a very simple manner. Wells’ innovation was the idea of a machine which would give the user mastery of Time itself. Moorcock also notes that Wells considered this to be his one great idea which he always felt he never exploited as fully as he wished. The need to make a living forced him to set down the story in some haste when it was accepted for serialisation in WE Henley’s New Review. (Moorcock’s introduction can be found in a recent collection London Peculiar and Other Nonfiction).

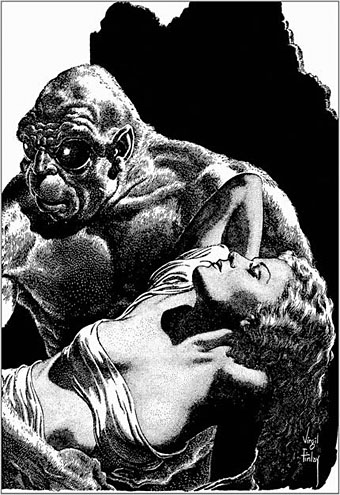

The other notable feature this time round—and this means more to me than it would to many other readers—was being struck by the way Wells’ story prefigures so much of the fiction William Hope Hodgson would be writing a decade or so later. It’s a commonplace among Hodgson scholars that The Night Land (1912) owes something to the scenes when the Time Traveller journeys beyond the age of the Eloi and Morlocks to a period when the Earth is dead and the Sun has swollen to a baleful giant. Some of the more cosmic moments of The House on the Borderland (1908) can also be traced back to these scenes. I’d argue that the Time Traveller’s earlier battles with the Morlocks prefigure and possibly influence similar battles in The Night Land, and the attacks of the Swine-Things in Borderland. There’s even a moment near the end of Wells’ story when the Time Traveller is menaced by giant crustaceans like those which infest Hodgson’s Sargasso Sea. This may not be a fresh observation but it’s not one I’ve seen elaborated before.

Regular readers will know it’s a habit here to seek out illustrations of favourite stories. In the case of The Time Machine there are hundreds to choose from so the following selection barely scratches the surface. Something I’d not noticed before when looking at comic strip adaptations is that none of the works derived from Wells’ story (George Pal’s film included) seem able to countenance the Time Traveller’s abandoning of Weena to the Morlocks when the pair become trapped outdoors at night; all show the Time Traveller doing his best to rescue her. William Hope Hodgson’s fiction is filled with rescues, sieges and the defence of the weak against marauding and inhuman forces; The Night Land concerns an epic and apparently suicidal rescue mission across the most inhospitable terrain imaginable. It may be stretching a point but it’s possible to see much of Hodgson’s fiction as being a riposte to this incident in Wells’ story.

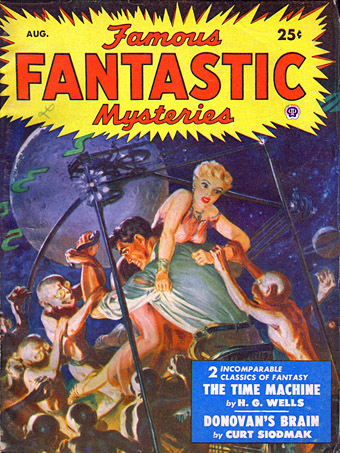

Illustration by George Saunders (August, 1950).

Recurrent points of interest in illustrations of Wells’ story are i) How is the Time Machine itself depicted? (The author’s descriptions are evasive), and ii) How are the Morlocks depicted? Wells describes them thus:

‘I turned with my heart in my mouth, and saw a queer little ape-like figure, its head held down in a peculiar manner, running across the sunlit space behind me. It blundered against a block of granite, staggered aside, and in a moment was hidden in a black shadow beneath another pile of ruined masonry.

‘My impression of it is, of course, imperfect; but I know it was a dull white, and had strange large greyish-red eyes; also that there was flaxen hair on its head and down its back. But, as I say, it went too fast for me to see distinctly. I cannot even say whether it ran on all-fours, or only with its forearms held very low.

George Saunders’ small Gollum-like creatures are closer to Wells’ conception than many later depictions. Saunders’ Weena, on the other hand, is far too tall for the equally diminutive Eloi.

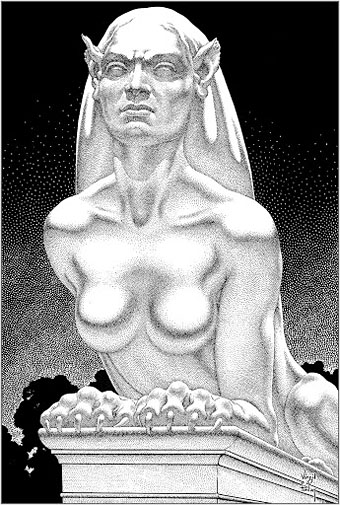

Virgil Finlay (1950).

This is still my favourite Time Machine illustration but then Finlay has a tendency to beat everyone when it comes to these assignments. His illustrations appeared inside the August, 1950 issue of Famous Fantastic Mysteries. Wells’ sphinx has wings which I imagine Finlay might have included if he wasn’t restricted by the space allowed for his illustration. He also provided the illustration of a Morlock below.

Virgil Finlay (1950).

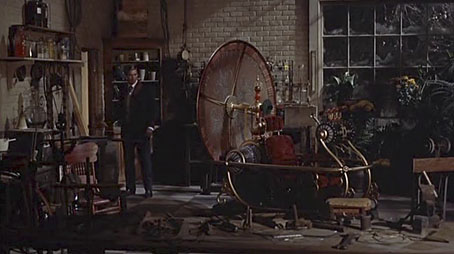

Rod Taylor as “H. George Wells”.

The Time Machine created by Bill Ferrari for George Pal’s film is for me the design that everyone has to beat. Wells was a great bicycling enthusiast and so describes his machine as having a saddle. Ferrari’s plush seat seems a more comfortable option for journeying millions of years into the future. (On a pedantic note: Pal’s film also makes some play with the Time Traveller departing for the future on “the eve of a new century”: December 31st, 1899. If you read any magazines from 1900 you’ll find that the late Victorians regarded 1901 as the first year of the 20th century.)

The dining house of the Eloi.

I always liked the way the air raid sirens from the 20th century were used as a summoning device for the Eloi even though it’s unlikely this use would have survived to the year 802,701. Minor quibbles aside, Pal’s film is a superb adaptation. Every so often I wish they’d kept Wells’ scenes of the dying earth but Wells would no doubt approve of the note of uplift at the end when the Time Traveller sets off again to rebuild civilisation. Doctor Macro has a page of posters and lobby cards for the film.

Les Edwards (1979).

Les Edwards gives us a spiky Time Machine and a view of the end of the world which Wells conveys in some memorable paragraphs:

‘The darkness grew apace; a cold wind began to blow in freshening gusts from the east, and the showering white flakes in the air increased in number. From the edge of the sea came a ripple and whisper. Beyond these lifeless sounds the world was silent. Silent? It would be hard to convey the stillness of it. All the sounds of man, the bleating of sheep, the cries of birds, the hum of insects, the stir that makes the background of our lives—all that was over. As the darkness thickened, the eddying flakes grew more abundant, dancing before my eyes; and the cold of the air more intense. At last, one by one, swiftly, one after the other, the white peaks of the distant hills vanished into blackness. The breeze rose to a moaning wind. I saw the black central shadow of the eclipse sweeping towards me. In another moment the pale stars alone were visible. All else was rayless obscurity. The sky was absolutely black.

Les Edwards (1979).

For those who’d like more there’s film poster art and some book covers here, while Golden Age Comic Book Stories has a comic strip version of the film script illustrated by Alex Toth here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Magic Shop by HG Wells

• HG Wells in Classics Illustrated

• The night that panicked America

• The Door in the Wall

• War of the Worlds book covers

Pal’s “The Time Machine” is a key part of my childhood and I agree that the time machine itself was a thing of beauty like no other. While I loathed nearly everything about it, Wells’ 2002 remake was notable (in my opinion anyway) for the unbelievably beautiful titular prop. Fabulous.

Excellent post on Wells and THE TIME MACHINE. I especially like your take on Hodgson and Wells, having thought that there was a link between NIGHT LAND and the end of the world scene. I have a personal tradition of seeing George Pal’s movie on December 31, which is my favorite ever movie adaptation of a Wells work. By the way, have you seen the Hallmark Entetainment miniseries, “The Infinite Worlds of H.G. Wells? It’s a TV adaptation of some of his stories, and it’s a DVD.

John: I’ve still not seen the 2002 version, it looked like the usual fare which invariably makes me want to track down the creators with a crowd bearing pitchforks and flaming torches.

Daniel: Thanks, I’d not come across the miniseries either. Filmmakers tend to remake the same novels over and over when many of Wells’ short stories would be equally suited to film adaptation. Wells himself wrote the screenplay for The Man Who Could Work Miracles in 1936, a lesser-known adaptation I’d recommend:

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0029201/

Have you seen “Time after Time’ not as bad as this makes it look… http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MY7Vz17STok

Nick: Yes, and always enjoyed it for its juxtaposing of 19th-century mores with 20th century ones. Also enjoy seeing Malcolm McDowell in a lead role.

Hey John, this is a tad off topic but since you mentioned “The House on the Borderland” that reminded me that you had talked about Savoy publishing an edition of Hodgson’s book. Are there still plans for that or has it fallen by the wayside?

Happy New Year!

That was something that was announced as forthcoming circa 1999 but which was displaced by other Savoy titles. Nightshade then did a very good edition of THOTB which rendered any Savoy edition redundant. When you have limited resources it makes sense to concentrate on publishing original works or titles which are far more scarce than anything by Hodgson. Unfortunately that 1999 announcement still circulates so I keep getting asked about it.

The whole “Dying Earth” cycle, Clark Ashton Smith and Jack Vance especially, owe a debt to Wells’ vision at the end of THE TIME MACHINE.

Also “Graphic Classics” has a collection of Wells’ stories illustrated by Dan O’ Neill, Skip Williamson, Shag, Antonella Caputo and others. Included are: “The Invisible Man”, “The Man Who Could Work Miracles”‘ “The Star”, “The Man With a Nose”, and more.

It seems that Wells was a bit of a graphic artist himself,check out THE DESERT DAISY, created when Wells was 13 years old, a portion of which is included in the above publication. I have and treasure a 1957 facsimile reproduction of it. And we must not forget the many doodle-like illustartions in EXPERIMENT IN AUTOBIOGRAPHY.

Oh, I apologize. It was just a random thought.

G: That’s okay. It’s one of the hazards of interviews: you’re asked what you have planned for the future, you say “I may be doing X” then people read the thing years later and want to know what happened to X.

This post has me researching seriously THE TIME MACHINE. When it appeared serially under a different title, before book publication, an episode of Wells’ vision of the end of the world was omitted from all book publications. This is the adventure of the kangaroo-rat men and giant insects. It is not known why Wells omitted this episode from later printings, perhaps because it was too fantastic, but it does give a fuller inevitability to Wells’ take on human history. This episode and the revised expanded version of “The Chronic Argonauts” is included in EARLY WRITINGS IN SCIENCE AND SCIENCE FICTION by H.G. Wells, edited byRobert Philmus and David Y. Hughes.

Yes, Moorcock details the history of the story in his introductory essay. When I first start reading Wells I found the title Chronic Argonauts to be very funny, the word “chronic” having evolved via its association with illness to a point where us schoolkids took it to signify something bad or unworthy.

In theory The Time Machine could have a huge amount of additional scenes before the Time Traveller’s return to the 1890s, something the film demonstrates by showing his stops before the leap into the distant future.