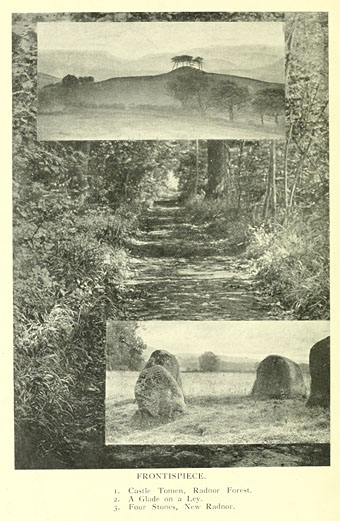

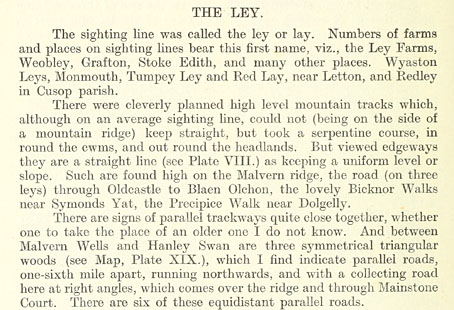

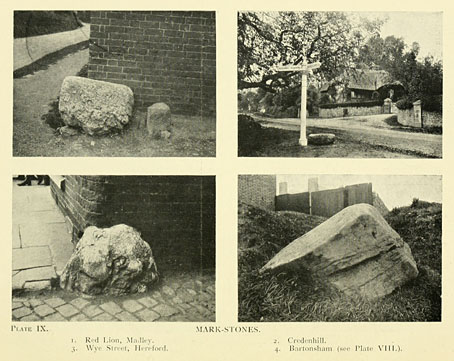

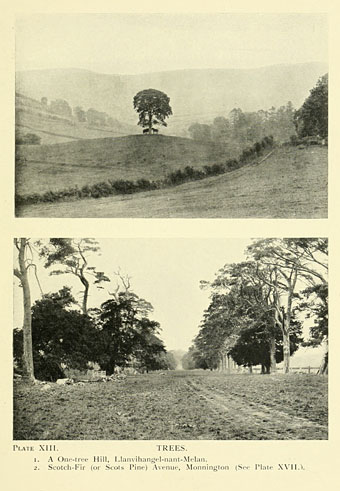

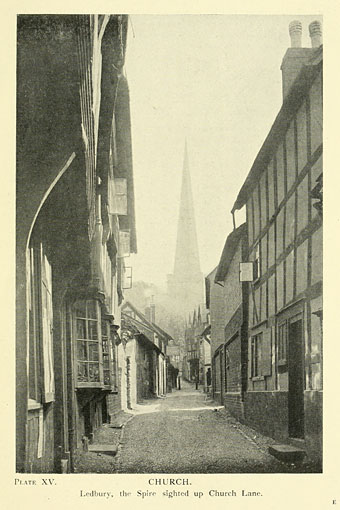

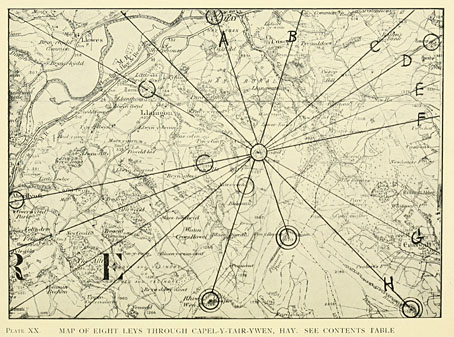

Continuing the Earth mysteries/megaliths theme, Early British Trackways: Moats, Mounds, Camps, and Sites (1922) by Alfred Watkins (1855–1935) was the first book in which the ley lines theory was proposed. Watkins was an amateur archaeologist (more a kind of early psychogeographer), photographer and writer who theorised that ancient Britons had marked the land with pathways connected by a variety of natural and man-made features: hills, mounds, trees, ponds, hillside notches and (of course) standing stones. Watkins coined the term “ley” after noticing that many of the lines connecting these features ran through villages or areas of land whose names ended in “-ley”, “-lay” or similar. The thesis was developed more fully in The Old Straight Track (1925), a book which became the ur-text for subsequent ley hunters. I’ve never seen any of Watkins’ books so it was interesting finding this short volume at the Internet Archive, not least because several of the photos appear in Mysterious Britain (1972) by Janet & Colin Bord, a classic guide to Britain’s sacred sites and folk rituals.

Watkins never regarded ley lines as having any mystic significance, he thought they were probably old trade routes. Archaeologists have never agreed with his suppositions, however, and Watkins himself might have disapproved of the conjectures added to his theories by John Michell in The View Over Atlantis (1969) which wedded ley line theory to feng shui to create the whole “lines of energy” idea. Whatever one thinks of Michell’s theories, that book and subsequent volumes put ley lines firmly into popular culture, and without them we wouldn’t have the references in Children of the Stones, Steve Hillage’s Green (1978) (pretty much a Michell-inspired concept album), Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass (1979) and so on. But this slim book is where it all begins.

Illustration by Roger Dean (1972).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Milbury souvenirs

• Children of the Stones

It is interesting how Watkins stuff has been rejected by main stream archaeologists, though they seem to have not even read him. His carefullness for insisting on five or more points, and his combination of media, seem to me worth working upon.

Hi John. I’m agnostic on the matter. One thing which works as both a pro and con for Watkins’ theory is that human beings are pattern-making creatures, so there’s a likelihood that the countryside might be marked with old tracks; equally, one could say that Watkins was making patterns of his own. (John Michell certainly was.)

Whenever I read a snub of a new theory that isn’t (say) violating physical laws I think of Robert Anton Wilson’s criticisms of the scientific establishment for too often valuing reputation (and funding) over the pursuit of new ideas. Heretical theories sometimes turn out to be the most accurate ones after all, as the example of Alfred Wegener shows.

Rather interestingly, I’ve just found that Somerville’s article in Antiquity was similtaneously published in The Straight Track Club and I presume he had submitted it. That has been rather well hidden detail.