…the growths of that garden were such as no terrestrial sun could have fostered, and Dwerulas said that their seed was of like origin with the globe. There were pale, bifurcated trunks that strained upwards as if to disroot themselves from the ground, unfolding immense leaves like the dark and ribbed wings of dragons. There were amaranthine blossoms, broad as salvers, supported by arm-thick stems that trembled continually.

And there were many other weird plants, diverse as the seven hells, and having no common characteristics other than the scions which Dwerulas had grafted upon them here and there through his unnatural and necromantic art.

These scions were the various parts and members of human beings. Consummately, and with never failing success, the magician had joined them to the half-vegetable, half-animate stocks on which they lived and grew thereafter, drawing an ichor-like sap. Thus were preserved the carefully chosen souvenirs of a multitude of persons who had inspired Dwerulas and the king with distaste or ennui. On palmy boles, beneath feathery-tufted foliage, the heads of eunuchs hung in bunches, like enormous black drupes. A bare, leafless creeper was flowered with the ears of delinquent guardsmen. Misshapen cacti were fruited with the breasts of women, or foliated with their hair. Entire limbs or torsos had been united with monstrous trees. Some of the huge salver-like blossoms bore palpitating hearts, and certain smaller blooms were centered with eyes that still opened and closed amid their lashes. And there were other graftings, too obscene or repellent for narration.

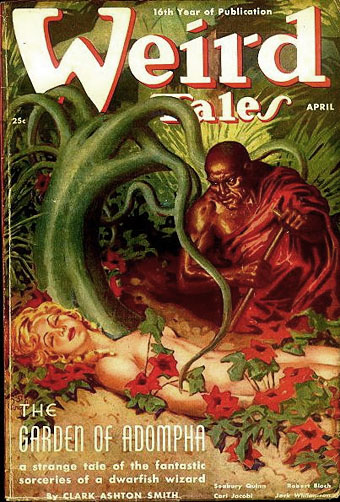

Thus Clark Ashton Smith in The Garden of Adompha, one of the stories in the author’s Zothique cycle which was first published in Weird Tales in April, 1938. Zothique was Smith’s contribution to the Dying Earth subgenre, sixteen stories set on the last continent in the final days of the Earth, and a home to no end of sorcery and cruelty. I’ve always enjoyed this subgenre, especially in the hands of Jack Vance whose later Dying Earth stories show the influence of Zothique, so these are some of my favourites among Smith’s prodigious output. The Garden of Adompha is a particularly grotesque piece, concerning the sequestered garden of the title to which King Adompha has undesirables removed. Once there his wizard, Dwerulas, drugs the victims and grafts parts of their bodies to the garden’s hothouse plants. Virgil Finlay’s cover painting downplays the horror somewhat, and Dwerulas’s supine prey, Thuloneah, looks like a very typical American girl, but then for a story that reads like a pulp equivalent of Octave Mirbeau it’s surprising it made the cover at all.

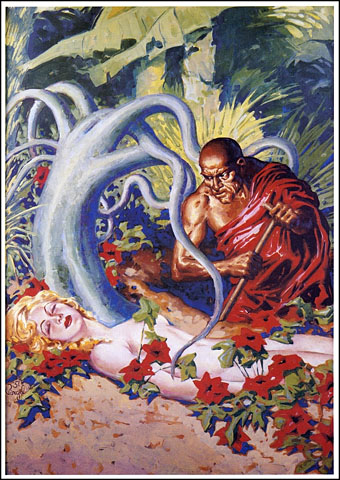

Re-reading some of Smith’s stories over the past week, The Garden of Adompha among them, there’s been the additional pleasure of searching for illustrations from their original publication. I knew that Virgil Finlay had painted this cover, one of the few cover features Smith received from Weird Tales, but Alistair Durie’s Weird Tales (1979) collection only has a monochrome reproduction. The always reliable Golden Age Comic Book Stories not only has a copy of Finlay’s original painting but also the interior illustration which looks like a litho drawing rather than the artist’s more usual scratchboard. The most recent book collection featuring the story was The Collected Fantasies Of Clark Ashton Smith Volume 5: The Last Hieroglyph (2010) from Night Shade Books. (I would have linked to the publisher’s page but their site seems to be broken.)

Update: Golden Age Comic Book Stories changed its name then vanished altogether. The picture links here have been updated.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Vathek illustrated

• The Vengeance of Nitocris

• The House of Orchids by George Sterling

• Haschisch Hallucinations by HE Gowers

• Odes and Sonnets by Clark Ashton Smith

• The King in Yellow

• Clark Ashton Smith book covers

On the subject of the Dying Earth, what do you think of Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun?

I don’t like Wolfe’s writing enough to want to tackle three volumes of the stuff. I know this will appall those who think his trilogy is the best thing evaaaar (and who no doubt think CAS is a hack in comparison) but there it is. A lot of the genre classics are things I’ve never read for similar reasons, despite working in the field for much of my time. I’ve always read very selectively in and out of the genres. The nice thing about Smith’s fiction is you see this stuff being built from the ground up at a time when anything was possible and these stories were all just “weird tales”. There’s a freshness even in the completely unscientific SF that you no longer find.

There would be blood drawn if I ever heard someone refer to Smith as a “hack” in my presence.

I really do despise the idiotic and oft repeated criticism of Lovecraft and his fellow writers that they’re just awful stylists that happened to have some decent ideas; as someone who has just exited the dull Babylon of Academia I’m generally horrified that these writers continue to be as overlooked as they are now. In today’s world I find Lovecraft infinitely more relevant that a writer like Henry James. While I not a big fan of Howard, I personally find that Smith’s writing can soar to the heights of decadent writers in his descriptions.

I guess I’m just bitching along the same lines as when I proclaimed that Arthur Machen should take the place of Thomas Hardy in the literary canon.

I don’t know whether anyone would criticise Smith that way–few people write about him at all–but seeing as how I still read complaints about Lovecraft being a bad writer it’s a safe bet. The thing that always rebukes the unexamined prejudice is that Lovecraft, Smith and Robert E. Howard are all in print today unlike many of their real hack contemporaries like Seabury Quinn.

There’s a lot to like about Smith’s writing beyond the story content, not least because he was a published and highly-praised poet before he started writing stories. That heightened, lyrical style was already well-established. I naturally tend to compare writing styles to art styles and see Smith’s style as being an equivalent in words of the intricacies and exaggerations of an artist such as Harry Clarke: lots of mannered poses, unusual flourishes and prodigious detail.

I read this week another of those tiresome “author’s rules for writing” that some writers feel is now a compulsory blog post; the first commandment was against using strange or rare words, an injunction that would discard almost all my favourite writers. Some people may be eager to consume prose that’s the equivalent of tepid minestrone soup but I never have been.

I had more or less made the same assumption; since critical opinion of Lovecraft is so condescending I imagined Smith, regrettably widely known as “one of Lovecraft’s circle of writers”, would receive the same treatment. Again with my damned personal opinions; I’ve always found Smith a more enjoyable read than Lovecraft and the superior writer.

I really love the Harry Clarke equivocation. I don’t remember where I read it, I imagine it was something decently basic such as a Joshi or Carter introduction, but the author expressed the opinion that much of Smith’s writing was “textual painting” as opposed to straight forward narrative. I thought it rang true enough.

Compulsory blog post…go do something useful, like smoke. As far as not using strange or rare words; I’m reminded of Steve Moore’s closing statement in his “Decades of Decadence” article. It was something along the lines that while these writers may often be dismissed as using purple prose, it may be worthwhile to read something above the simplistic fare that we call literature today. That was a stretched paraphrase but I think I may have captured the gist. I also remember Moore saying in an interview that Smith was his favorite writer, and if you can’t trust him…

I once bought a de Grandin paperback for thirty dollars; I only made it through one story before it was resigned to a resting place on the bookshelf in my parent’s house. :(

I like Lovecraft and Smith too but let’s not go overboard and pretend that they’re in the same league as Henry James or Thomas Hardy. Literary snobbery has nothing to do with it.

Stephen: I’d never make such a comparison since different groups of writers are working towards different ends, and often employing very different means.

G: Complaints about purple prose have never made sense to me, mostly for the reasons cited above. The implication is that there’s only one good and useful way to use words, and that any deviation from the path is heresy or bad form. This is nonsense but the sentiment persists.