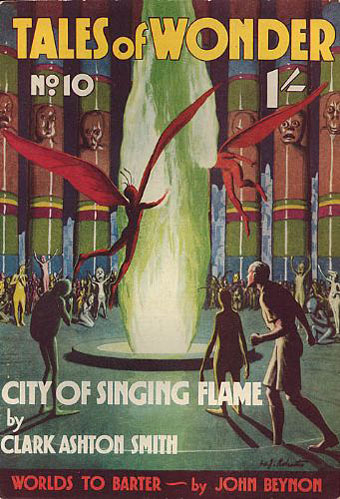

Wonder Stories, July 1931. Illustration by Frank R. Paul.

Looking over Bruce Pennington’s artwork this week sent me back to some of my Clark Ashton Smith paperbacks, many of which sport Pennington covers. One of my favourite Smith stories, The City of the Singing Flame, is also one of his finest pieces, and a story that Harlan Ellison has often referred to as his favourite work of imaginative fiction.

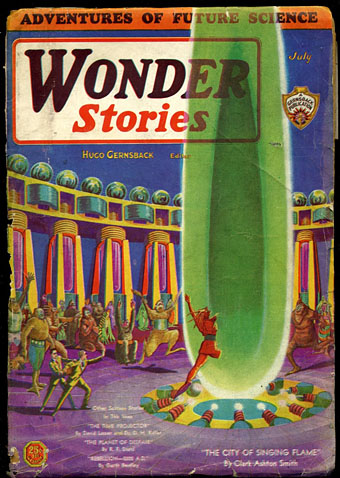

Tales of Wonder, Spring 1940. Illustration by WJ Roberts.

The story as it’s known today was originally a shorter piece, The City of the Singing Flame, followed by a sequel, Beyond the Singing Flame; both stories were published in Wonder Stories magazine in July and November of 1931, then as one in Arkham House’s CAS collection Out of Space and Time in 1942. The two-in-one story is now the definitive version.

Smith’s tale concerns the discovery of a dimensional portal somewhere in the Sierras. Beyond this there lies a path leading through an otherworldly landscape to a colossal city peopled by a race of mute giants. A temple at the heart of the city protects the prodigious green flame of the title, an eerie and alluring presence whose siren call draws creatures from adjacent worlds who prostrate themselves before the flame before immolating themselves in its fire. A narrator, Philip Hastane, give us details of diary entries from a friend who discovered the portal, and who subsequently has to decide whether to resist the lure of the mysterious flame or follow the other creatures into the fire. More than this would be unfair to divulge if you’ve never read Smith’s remarkable piece of fiction.

Wonder Stories, July 1931. Illustration by Frank R. Paul.

Re-reading the story again this week I was mostly struck by what might be regarded as a psychedelic quality to much of the description and the transcendental impetus which drives the narrative. Jorge Luis Borges in Kafka and his Precursors noted how any sufficiently powerful artist fixing in their work a previously unexamined quality gains a train of previously disparate precursors, all of whom are thereafter connected by that quality. This syndrome can apply to art movements as much as artists or writers. Just as stories prior to Kafka can be deemed Kafkaesque, so painting before Surrealism can be deemed Surreal, and art prior to the 1960s can be regarded as psychedelic. Here’s Clark Ashton Smith sounding like a mescaline voyager in 1931:

Any attempt to describe the experience would be foredoomed to futility, since it seemed that a whole range of new senses had been opened up in me, together with corresponding thought-symbols for which there are no words in human speech. I was no longer Philip Hastane, but a larger, stronger and freer entity, differing as much from my former self as the personality developed beneath the influence of hashish or kava would differ. The dominant feeling was one of immense joy and liberation, coupled with a sense of imperative haste, of the need to escape into other realms where the joy would endure eternal and unthreatened.

My visual perceptions, as we flew above the burning, lucent woods, were marked by intense, aesthetic pleasure. It was as far above the normal delight afforded by agreeable imagery as the forms and colours of this world were beyond the cognition of normal eyes. Every changing image was a source of veritable ecstasy; and the ecstasy mounted as the whole landscape began to brighten again and returned to the flashing, scintillating glory it had worn when I first beheld it.

References to drugs are scattered throughout the narrative, mostly in symbolic terms:

My homeward journey was blurred and doubtful as the wanderings of a man in opium-trance; and the music sang behind me, and told me of the rapture I had missed, of the flaming dissolution whose brief instant was better than aeons of mortal life….

But later we have a detail which implies some personal experience:

The exhaustion that still beset me was too profound to permit of thought or feeling; it was like the first reaction that follows the awakening from a drug-debauch.

I’ve never read much of Smith’s life so I’ve no idea how much of his fiction, if any, was fuelled by actual drug experiences. But he did write a long poem in 1920, The Hashish Eater, or The Apocalypse of Evil, which brought him to the attention of HP Lovecraft, and many of Smith’s other stories feature similar references. Most of those references, however, tend to be part of the exotic detail with which he encrusted his fiction. In City of the Singing Flame we have a richer sense of the expanded consciousness which occurs at the height of hallucinogenic experience. Beyond the druggy atmosphere there’s also some fantastic invention: the Cyclopean city and its strange visitors (none of whom are ever a threat to the human observers), the otherwordly landscapes and transhuman sense impressions, and the unseen creatures intent on destroying the home of the Singing Flame who attack the city with a walking metropolis of their own.

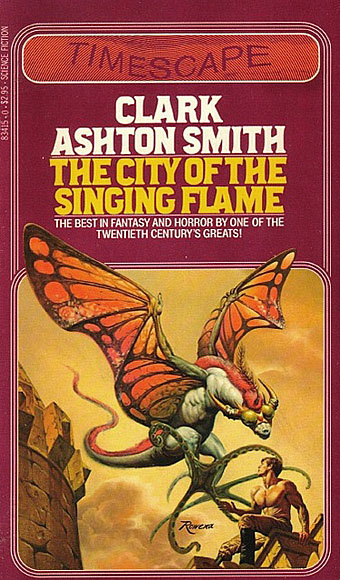

The City of the Singing Flame, 1981. Cover by Rowena Morrill.

It’s a shame Bruce Pennington didn’t provide a cover for the Panther paperback which reprinted this story, many of the attempts at illustration fail to do Smith’s vast and bedizened imagination any justice at all. Frank Paul’s conception of the flame is far too small and he also gives the scene a science fictional gloss which doesn’t match any of Smith’s descriptions. Rowena Morrill, on the other hand, does a superb job depicting the moment when the narrator, Hastane (here looking hunkily attractive), encounters a pair of benevolent moth-like aliens who carry him to the city.

The City of the Singing Flame has been reprinted many times since 1942 so it’s easy to find. The leading Clark Ashton Smith website is still Eldritch Dark, and they have a copy of the entire story here should you wish to discover the secret of the green fire. It’s a trip, in more ways than one.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Vengeance of Nitocris

• Haschisch Hallucinations by HE Gowers

• Odes and Sonnets by Clark Ashton Smith

• The King in Yellow

• Clark Ashton Smith book covers

Haven’t read the story yet but from all the descriptions and hints you give it sounds like a cross of amongst other stories H Rider Haggard’s She, Norman Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus and Hodgson’s House on the Borderland

It’s similar to the Hodgson although without the atmosphere of doom and horror. Smith could certainly do the doom and horror but this story is remarkably free of that, and also free of the angst of Arcturus. As to the latter I’m not sure how widely-read that would have been in 1931, the first edition wasn’t a big seller, it’s reputation was established much later.

Oh, and it’s David Lindsay. Norman was the Aussie artist. :)

Sorry Freudian slip there I’ve been to Norman Lindsay’s House and his name is more prominent in my subconcious than Davids.

Check out this statue he did there http://www.normanlindsay.com.au/tours/insidethegallery.php

My personal favorite of the old Weird circle.

Is your part of UK burning too?

No, but thanks for the concern. :) My area is a leafy suburb, it’s the last place here there’d be a riot.