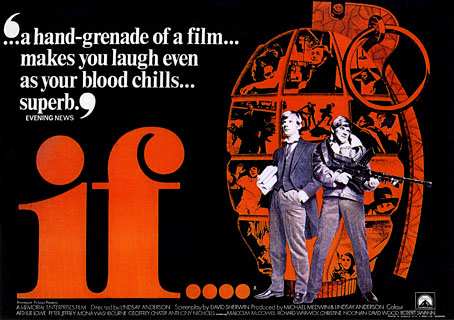

Lindsay Anderson‘s masterpiece, If…., is finally given a DVD release in the UK in June. Anderson’s film—the dramatic resistance to authority by three boys at an unnamed British school—was made in 1968 but I didn’t get to see it until (as I recall) 1977. I was 15 at the time and feeling increasingly desperate and hidebound by school-life so this film was explosive in its psychological impact as well as its story (that grenade on the poster was very apt). Given my age and the year, I’m supposed to have cult yearnings toward the wretched Star Wars but it was If…. that made the lasting impression.

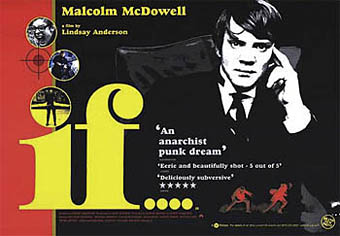

Poster for the 2002 re-release.

If…. was important for a number of reasons, not all of them obvious during that first viewing. I didn’t go to an all-boys public school (note for Americans: “public school” in Britain actually means an expensive, private establishment) but my grammar school had been an all-boys place a few years before I arrived. Some teachers wore gowns at assembly and many of the older teachers there were of a rigid, brutalist mindset exactly like the ones in Anderson’s film. Bullying was endemic, uniform rules were enforced to a degree that would make an army colonel proud and you stood out from the crowd at your peril; I had friends there but I hated every minute. So here comes young Malcolm McDowell on the television screen, effortlessly charismatic and insouciant in his first film role, portraying the ultimate Luciferan rebel, one who (as Anderson writes in the screenplay preface below) says “No” in the face of overwhelming odds. Reader, I identified so very much…. The famous ending (borrowed from Jean Vigo’s Zéro de Conduite) where Mick and the other “Crusaders” fire guns and throw grenades at the rest of the school was headily wish-fulfilling. (And given recent events, you’ll also see below that Anderson and screenwriter David Sherwin regarded that ending as metaphorical, not literal.)

That was the immediate reaction. Later I came to recognise the quality of the film’s production: Miroslav Ondricek’s photography, the great cast and music, the careful pacing and sequential structure (the film is in eight parts, all numbered and titled), and the occasional moments of unexplained strangeness. Then there’s the line that can be traced from If…. to that other film of youthful rebellion, A Clockwork Orange, since Stanley Kubrick said it was McDowell’s performance in If…. that gave him the role in the later film. I’ve noted elsewhere how Kubrick slyly acknowledged this during the scene in A Clockwork Orange when Alex goes to buy a record and we briefly glimpse the sleeve of the Missa Luba album by Les Troubadours du Roi Baudouin. The ‘Sanctus’ track from that album is heard at several key moments throughout If….

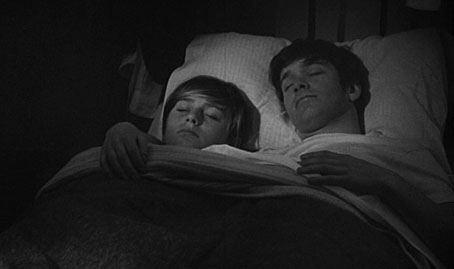

Finally, I have to note that If…. included this moment, listed as Shot 541 in the published screenplay:

*Shot 541. (Black and white stock, sepia tint.) Dissolve to the Junior Dormitory. It is dark. Boys are asleep in their beds. Camera pans slowly along the line – MARKLAND, MACKIN, ending on a high angle close-up of a bed in which BOBBY PHILLIPS is lying, WALLACE’S arm around him, very peaceful.

Two boys in bed together, and no one bats an eyelid. If…. was not only the first film to show the frequently homosexual character of all-boys schools but it did so in a completely matter-of-fact manner; there were even “bad” gay characters (the whips) as well as “good” ones. Shot 541 arrived for me at a time when I was becoming increasingly aware of my own proclivities. I would have caught on sooner but at our dreadful school being gay was the worst thing you could possibly be, so any thoughts along those lines were deeply repressed. In the Seventies the only gay people on television were always outrageously camp (and middle-aged) comedians that I wasn’t ever going to identify with. Shot 541 was a small message from the future that delivered a shock of recognition although I didn’t articulate it as such, it only made me “feel funny inside”. I thought about that shot for a very long time afterwards but somehow managed to avoid wondering what it meant.

If…., shot 541.

Lindsay Anderson was gay, which is partly why the film is so even-handed and ahead of its time. At the end of the film we see that Mick and his new unnamed girlfriend have teamed up to fight authority and so too have Wallace and Bobby. Malcolm McDowell says that Anderson never really came to terms with his sexuality but this isn’t so surprising when gay sex had only been partially decriminalised the year before they made the film. For men of Anderson’s generation being honest to yourself or to others wasn’t always an option but in his art at least he managed to be true to his feelings.

So…now one has to ask when we get the sequel, O Lucky Man!, on DVD?

See also:

• Mark Sinker’s BFI Film Classics book

• A detailed fan site

• The man who gave me a slap in the face: “Ten years after Lindsay Anderson’s death, Malcolm McDowell explains why he can’t let go of the director who changed his life.”

• ‘Lindsay could be cruel. He was like an avuncular martinet’: “Many of the small players on Lindsay Anderson’s If…. became big shots in the movie industry. As the 1968 classic is reissued, Daniel Rosenthal talks to them about the director who became their mentor.”

• Anarchy in the UK: “Lindsay Anderson’s If…. encapsulated the radical spirit of 1968. But it was only the start of a trilogy that anatomised a faltering nation.”

Notes for a Preface by Lindsay Anderson

Although both David Sherwin and I went to (different) English Public Schools, If…. is not to be taken as an autobiographical film, at least not in a narrow or a literal sense. Of course, there are autobiographical elements in the script. For my part, I well remember Fryer, the tall, distinguished College prefect of Cheltondale in winter term 1936, standing at the door before house prayers and shouting at Hughes Hallett beside me: ‘Hallett damn you, stop talking!’ And the Reverend SoandSo certainly had those nasty habits of smacking you suddenly on the back of the head, and twisting your nipples, if you were unfortunate enough to land in his Maths set.

But such facile tags as ‘the Private Hell of the Public Schools’ (Sunday Graphic) or ‘Hatchet job on the Public School system’ (Sight & Sound), are misleading. Essentially the Public School milieu of the film provides material for a metaphor. Even the coincidence of its making and release with the worldwide phenomenon of student revolt was fortuitous. The basic tensions, between hierarchy and anarchy, independence and tradition, liberty and law, are always with us. That is why we scrupulously avoided contemporary references (on a journalistic level) which would date the picture; and why it is completely unimportant whether its slang, its manners, or its details of organisation are true to the schools of this year or that. And this is why the film has been understood recognised by so many people, of so many ages, and so many countries.

*

We specially saw Zéro de Conduite again, before writing started, to give us courage. And we constantly thought of Brecht, and his definition of the ‘epic’ style. David referred to Kleist from time to time. John Ford (‘old father, old artificer’) and Humphrey Jennings (romantic-ironic conservative) were in the bloodstream.

I have been asked very often about the use of colour in the film or rather the use of monochrome. When Shelagh Delaney and I were working on the script of The White Bus, which was also a poetic film, moving freely between naturalism and fantasy, I remember suggesting that it would be nice to have shots here and there, or short sequences, in colour (it was otherwise a black and white film). The idea also appealed to Miroslav Ondricek, and we did it. Almost no one has seen The White Bus, but I like the film very much, and I think the idea was successful.

It was this precedent that gave me the assurance when Mirek said that with our budget (for lamps) and our schedule he could not guarantee consistency of colour for the chapel scenes in If…. to say, ‘Well, let’s shoot them in black and white.’ In other words it was not (of course) just a matter of saving time and/or money. The problem of the script seemed to be to arrive at a poetic conclusion, from a naturalistic start. (Like any fairy-story or folk-tale). We felt that variation in the visual surface of the film would help create the necessary atmosphere of poetic license, while preserving a ‘straight’, quite classic shooting style, without tricks or finger-pointing.

I also think that, in a film dedicated to ‘understanding’, the jog to consciousness provided by such colour change may well work a kind of healthy Verfremdungseffect, an incitement to thought, which was part of our aim.

And finally: Why not? Doesn’t colour become more expressive, more remarked if drawn attention to in this way? The important thing to realise is that there is no symbolism involved in the choice of sequences filmed in black and white, nothing expressionist or schematic. Only such factors as intuition, pattern and convenience.

*

This script, as printed here, represents the definitive version of If…. Unfortunately there is no guarantee that readers will have seen or will be able to see exactly the film we made. It depends where you live. Various versions, differing in various ways from the original, are now circulating through the world. The cuts and modifications demanded by national censorships would indeed provide an interesting footnote to a social history of 1969. In Britain the Board of Film Censors broke precedent by permitting the glimpse of Mrs. Kemp’s pubic hair as she wanders naked down the dormitory corridor; but as compensation they demanded the substitution at the start of the shower scene, of an alternative take in which the discreet use of towels prevented an equivalently frank look at the boys. Needless to say the film was forbidden to anyone under the age of sixteen.

The American Board of Censors also gave the film an ‘X’ certificate, but passed it unmutilated. The distributors, however, were not prepared to accept the X-rating outside New York, and cut the picture (again Mrs. Kemp and the showers) for an ‘A’ rating. Having read about this by chance in Variety, we insisted that alternative takes (the same shower scene and a shot of Mrs. Kemp from the rear) be substituted.

Plainly, in this third quarter of the twentieth century since Christ, the naked figure is still the object of deepest alarm. Plainly, also, social reaction, puritanism and philistinism are closely linked. Australia cut the film even for its premiere performance at the Sydney festival and Italy refused to allow it to close the festival at Taormina. (The Italian ban was later rescinded as a result of vigorous protests by the Press.)

Eire was alarmed over various sexual references in the scene in Johnny’s study; and South African citizens are not allowed to watch Wallace licking his pinup, or to hear Mick dreaming of walking naked into the sea with her, making love once, and then dying.

The only instance of purely political censorship so far reported (apart from Portugal, where the film cannot be shown at all) seems to be from the Colonels’ Athens, where, as far as we can make out, the film has been showing with its final sequence completely excised.

Many people contribute to the making of a film. Many of them get mentioned on no list of credits. For If…. I would like to record my thanks to Seth Holt who first introduced me to David Sherwin, John Howlett and Crusaders; to our patrons, Albert Finney of Memorial and Charles Bluhdorn of Paramount; to Marvin Birdt who stuck his neck out and recommended the script; to my friend Daphne Hunter who suggested the title; people like Peter King and Gerry Lewis, and Mort Hoch who committed themselves to the picture and helped us to get it on the screen; and, of course, David Ashcroft, Headmaster of Cheltenham College, whose liberal understanding and generous help in the creation of a work of art give the lie to facile criticisms of the system of education he believes in. Floruit, Floret, Floreat!

I remember also, most gratefully, Pat Moore, for his efficient and effective explosions; Peter Brayham for his fight choreography; Sergeant Instructor Rushforth for his beautiful performance on the bar, and Michael White and Malcolm Miles who helped us out so well on their motor-bikes on the Cheltenham-Tewkesbury road.

*

Essentially the heroes of If…. are, without knowing it, old-fashioned boys. They are not anti-heroes, or drop-outs, or Marxist-Leninists or Maoists or readers of Marcuse. Their revolt is inevitable, not because of what they think, but because of what they are. Mick plays a little at being an intellectual (‘Violence and revolution are the only pure acts’, etc.), but when he acts it is instinctively, because of his outraged dignity, his frustrated passion, his vital energy, his sense of fair play if you like. If his story can be said to be ‘about’ anything, it is about freedom.

In this sense Mick and Johnny and Wallace, and Bobby Phillips and the Girl are traditionalists. It is they, not their conformist elders nor their conformist contemporaries who speak the tongue that Shakespeare spoke (‘We must be free or die’). ‘England Awake,’ Johnny cries in the gym. And Mick: ‘We are not cotton-spinners all: Some love England and her honour yet! ‘ and Wallace, as he lunges, ‘Death to tyrants! ‘ They are very, I suppose fatally, romantic. Theirs is still: ‘The homely beauty of the good old cause.’

Far indeed from filling me with dread, I find the last sequence of the film exhilarating, funny (its violence is so plainly metaphorical), a bit shocking, magnificent (when the Headmaster is shot between the eyes), and finally sad. It doesn’t look to me as though Mick can win. The world rallies as it always will, and brings its overwhelming firepower to bear on the man who says ‘No.’

Charge once more then, and be dumb;

Let the victors when they come,

When the Forts of Folly fall,

Find thy body by the wall!

LINDSAY ANDERSON

November 1969

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Juice from A Clockwork Orange

• Alex in the Chelsea Drug Store