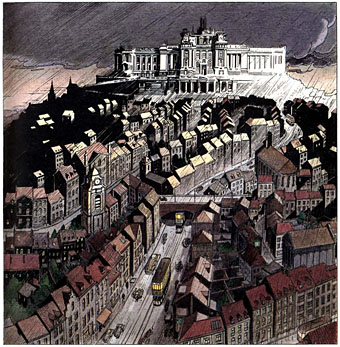

The Palace of Justice, Brussels.

Brüsel (1992) by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters follows La route d’Armilia as the next major work concerning the Cités Obscures. As with La Tour, this is a longer story where it isn’t immediately apparent that we’re in the Obscure World at all, although Brüsel is clearly an alternate version of our Brussels. The unfinished Palace of the Three Powers in the city centre is modelled on the Palace of Justice in Brussels, and both buildings share architects by the name of Joseph Poelaert.

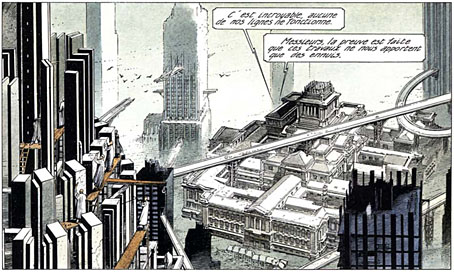

The Palace of the Three Powers, Brüsel.

Brüsel is a “small man” tale of Constant Abeels, a would-be shopkeeper preparing to launch a business selling a new and modern innovation: plastic flowers. Abeels suffers from a persistent cough, and it’s a combination of his health problems and business problems—the water for the shop is disconnected—that causes him to become enmeshed in schemings to radically transform the city, and the resistance to those plans. The tale is also a satire on the overly-optimistic march of progress of the late 19th and early 20th century, with all the problems of trying to impose sudden architectural change on a change-averse community. Inhabitants of Brussels have a long history of sudden architectural change, the huge Palace of Justice being constructed only after residents of the area had been forcibly evicted. In the 1950s and 60s, the flattening of old quarters in order to build New York-style office blocks was so destructive that the French coined the term “Brusselisation” to describe a brutal remodelling of a city against the wishes of its citizens.

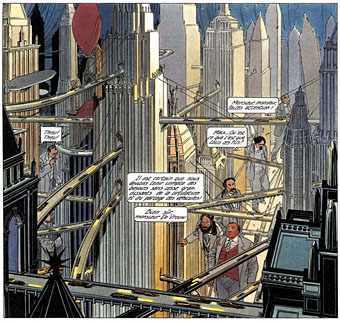

The city planners wandering through a model of the future city.

Schuiten and Peeters show Brusselisation at work in its most extreme form, with a city of winding streets completely demolished and replaced by soaring Art Deco skyscrapers. A small core of residents are against this, among them a young woman, Tina Tonero, who Abeels meets at the Palace, and who works with a resistance group daubing slogans on posters which show the city of the future. If there’s a recurrent flaw in Schuiten and Peeters’ stories it’s the continual ease with which attractive young women fall immediately for not-so-attractive older men, with Brüsel being another example of this pattern. One occurrence would be passable but it seems to happen so often it starts to look more like wish-fulfilment for the reader than realistic behaviour, especially in Brüsel when Tina manages to lose most of her clothing at an opportune moment.

The Palace now surrounded by new construction.

This complaint aside, Brüsel casts a satiric eye over all of its characters and regards without sentiment the unhealthy city of the past, where the miasmas from the river give Abeels his persistent cough, and the hospital where nuns apply leeches to their patients. The new hospital which replaces the old isn’t much better when the doctors are inattentive cranks, if they’re present at all. The careful reader is rewarded with some subtle connections to earlier stories: in the airship office of the oligarch de Vrouw we see the painting of the Tower of Babel from La Tour, a symbol of the businessman’s hubris. In the modern hospital later on there’s a glimpse of an older Robick from La fièvre d’Urbicande, now muttering to himself about the Network while he scribbles in a book, a victim of prior architectural squabbles. Schuiten and Peeters love their buildings but they’re fully aware that in the Obscure World, as in our own, the reshaping of cities is never trouble-free.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The fantastic art archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• La route d’Armilia by Schuiten & Peeters

• La Tour by Schuiten & Peeters

• La fièvre d’Urbicande by Schuiten & Peeters

• Les Murailles de Samaris by Schuiten & Peeters

• The art of François Schuiten

• Taxandria, or Raoul Servais meets Paul Delvaux

One thought on “Brüsel by Schuiten & Peeters”

Comments are closed.