A recent conversation with Evan J Peterson touched on the subject of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Evan is currently working on something based on the novel and—in the interests of disclosure—he wrote a very flattering piece about these pages recently. In addition to this, Peter Ackroyd’s latest book works his familiar intertextual games with the same story, placing the monster creator in London where he meets various significant literary types. Andrew Motion reviewed the latter this week and wasn’t impressed.

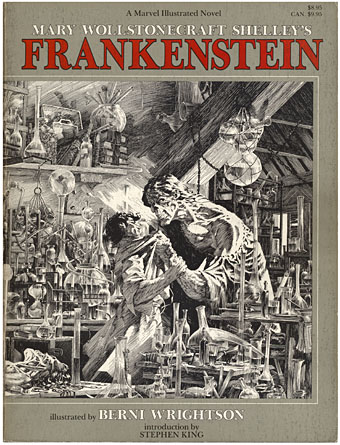

Which preamble brings us to Berni Wrightson’s treatment of the story and a work which was a major inspiration for my HP Lovecraft comics and illustrations. Wrightson’s illustrated edition of Shelley’s complete novel was published in 1983 with an introduction by Stephen King. I’d admired Wrightson’s technique for years but wasn’t always impressed by his subject matter which tended to revolve around the stock selection of favourite American horror characters—vampires, werewolves, zombies and so on—while much of his early art was indebted to the EC horror comics which never interested me at all. Jokey horror has always seemed to me a debased and neutered horror, horror-lite, and yes, that includes plush Cthulhus and the rest of that tat.

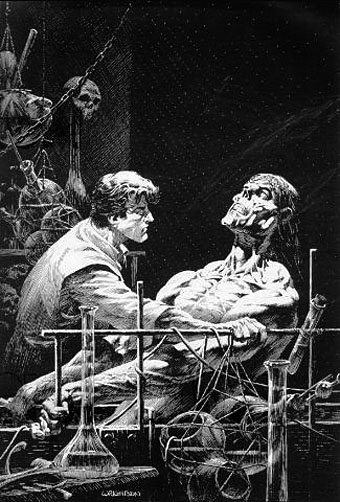

So the immediate attraction of the Frankenstein book was seeing Wrightson take the story back to its origins and treat it seriously. Frankenstein—creator, monster and myth—has been subject to as much degradation as Dracula over the past century which made Wrightson’s approach very welcome. Crucially, it also gave me the key to interpreting Lovecraft visually. It was very evident that his drawings owed a debt to a favourite illustrator of mine, Gustave Doré; two of the pieces were almost straight copies of Doré drawings from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. In terms of overt influence, Wrightson’s book is dedicated to the great Roy G Krenkel, one of the finest fantasy illustrators of the early 20th century. I wasn’t aware of it at the time but Wrightson’s style here also owes much to American illustrator Franklin Booth (1874–1948), one of Krenkel’s own influences. If the monster in his drawings had a touch of the lumbering EC zombie about its features that was allowable given the other influences at work, and besides, his compositions are perfect. Once I started work on my Lovecraft drawings I quickly found an approach that suited my own obsessions with fine line and detail. But it was Wrightson’s example which pointed the way.

The only problem discussing this is that the copies available on various sites, including Wrightson’s own gallery pages, don’t do the drawings much justice at all. (There’s a large copy of one picture here.) Where the more detailed pieces are concerned you’ll have to try and find a copy of the book. This year is the 25th anniversary of the book’s publication so Dark Horse Comics will be publishing a hard cover edition in October 2008. In addition, Darkwoods Press have announced an “ultimate edition” which will reprint all the artwork (some drawings weren’t used) with quality reproduction. No further information about that, however, and given that they’ve having to source all of the original drawings it may be a while before it appears.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Berni Wrightson in The Mist

• The monstrous tome

• Franklin Booth’s Flying Islands

Hello John,

Being raised purely on British comics I never encountered Wrightson’s art until reading Stephen Sennitt’s history of horror comics, Ghastly Terror: the few examples in there were pure gothic and most enticing, so I look forward to purchasing the reissued Frankenstein when it emerges.

As for Ackroyd, I’ve not kept up with his work in recent years: Dan Leno and The Last Testament of Oscar Wilde I thoroughly enjoyed, but now he seems to be the unofficial cultural guide for London, a far cry from the boozy figure spied within the pages of The Edge, corousing around town with Moorcock and Sinclair…

Martin.

Hi Martin. I missed Wrightson’s work in Swamp Thing since my teenage interest in comics didn’t last very long and I never found the horror comics of the time a match for horror fiction or cinema. But I enjoyed Wrightson’s work in The Studio book circa 1979, another big inspiration which showcased his work along with Jeff Jones, Mike Kaluta and Barry Windsor Smith. After that I started to look out for his work.

I’ve not kept up with Ackroyd either although I did pick up a book of his collected non-fiction recently. As to the fiction, Hawksmoor is the one to go for (not least for the debt it owes to Iain Sinclair) although all the early novels are worth a look. In fact I usually recommend reading Hawksmoor alongside Sinclair’s Lud Heat which was its inspiration. Last novel of Ackroyd’s I read was The House of Doctor Dee, another act of period ventriloquism and temporal cross-cutting which didn’t really live up to its promise.

‘Period ventriloquism’ sums it up perfectly, John. It appears to be fashionable now for a writer to take the base facts of history and weave the known story around them, rather than using said facts to go off into uncharted territory. Sinclair seems to keep up the momentum, but too much of his work digested too quickly can make the reader bloated. Voice of the Fire remains my favourite work in this area, and we can expect Mr Moore’s long-anticipated follow-up to blow the roof right of the museum.

Cheers,

Martin.

Hello, John! Thank you for giving me the shout-out and link in your blog, and for mentioning my book. Intertextuality, indeed. I hope that I can help elevate the Frankenstein myth rather than further degrade it. Anything could be better than reducing the monster to a breakfast cereal: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franken_Berry

Even so, I think a certain degree of camp is inevitable and enjoyable in a post-James Whale [not to mention postmodern] treatment of the story. Under the right circumstances, the kitsch and frivolity can become a pleasant backdrop for something utterly horrifying to happen suddenly in the foreground.

Yours,

Evan

Hi Evan. It’s the Franken Berry tendency I take issue with, that peculiar impulse to render everything cute. Is this a particularly American thing? It often seems that way although it was Brits that gave us Count Duckula… I wouldn’t criticise James Whale for a moment, Bride of Frankenstein is a masterpiece.

I forgot to note earlier when I mentioned Wrightson and The Studio that the artists who produced that book did a signing tour in the late Seventies which included a visit to Savoy’s Peter St. shop in Manchester. Dave B used to get famous visitors to sign the wall so Bernie Wrightson’s signature was there for years beneath the encrusted grime and shrinkwrapped comic books.

Hi, John

I’ve had this Wrightson work for more than 20 years and, even today, it continues to amaze me, since I’m an aficionado of black and white works, making a lot of them myself (although I’m using more black pens than brush strokes).

I consider FRANKENSTEIN to be the maximum Wrightson work, I don’t think he did anything better than this ever since.

That’s it, friend, it was nice seeing those pieces in your page. I’m rushing back home and see the work all over (yet again!).

Best regards

I think that the reduction of every cultural icon to something collectible and nonthreatening is an American thing, but it’s not a particularly American thing. The Japanese still have us beat there. I have a plush model of a flesh-eating bacterium at home, complete with embroidered fork and knife and plastic eyes. I couldn’t resist it.

Heh, yeah, the Japanese are masters of rendering the entire world cute and fluffy. I wonder if they’ve done any plush tentacle porn yet.

Márcio: I agree this is a high point in Wrightson’s work. As definitive in its own way as Harry Clarke’s Poe.