“What sort of criticism is it to say that a writer is pessimistic? One can name any number of admirable writers who indeed were pessimistic and whose writing one cherishes. It’s mindless to offer that as a criticism. Usually all it means is that I am stating a moral position that is uncongenial to the person reading the story. It means that I have a view of existence which raises serious questions that they’re not prepared to discuss; such as the fact that man is mortal, or that love dies. I think the very fact that my imagination goes a greater distance than they’re prepared to travel suggests that the limited view of life is on their part rather than on mine.”

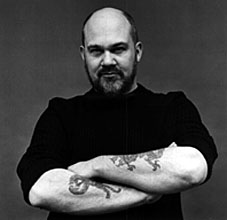

Thomas Disch castigating a science fiction readership which often regarded his work with a disdain born of narrow expectations. Disch (left), who took his own life a few days ago, was one of the New Worlds group of writers who frequently caused consternation among the kind of readers who only ever want to read about future technology. He was also much more than that, of course, and he wrote a lot more widely than most genre writers but it’s for his sf novels that he’ll be remembered. Rather than attempt another encomium I thought it far better to post a Charles Platt interview from 1979 which gives an insight into Disch’s character as a man as well as a writer. This was one of a number of interviews Platt conducted with leading sf writers during the late Seventies, published as Who Writes Science Fiction? in the UK (by Savoy Books) and Dream Makers: The Uncommon People who Write Science Fiction in the US.

Thomas Disch castigating a science fiction readership which often regarded his work with a disdain born of narrow expectations. Disch (left), who took his own life a few days ago, was one of the New Worlds group of writers who frequently caused consternation among the kind of readers who only ever want to read about future technology. He was also much more than that, of course, and he wrote a lot more widely than most genre writers but it’s for his sf novels that he’ll be remembered. Rather than attempt another encomium I thought it far better to post a Charles Platt interview from 1979 which gives an insight into Disch’s character as a man as well as a writer. This was one of a number of interviews Platt conducted with leading sf writers during the late Seventies, published as Who Writes Science Fiction? in the UK (by Savoy Books) and Dream Makers: The Uncommon People who Write Science Fiction in the US.

Thomas M Disch by Charles Platt

New York, April 1979

NEW YORK, city of contrasts! Here we are on Fourteenth Street, walking past The New School Graduate Faculty, a clean modern building. Inside it today there is a fine museum exhibit of surreal landscape photography, but the drapes are permanently closed across the windows because, out here on the stained sidewalk, just the other side of the plate-glass, it’s Filth City, peopled by the usual cast of winos, monte dealers. shopping-bag ladies festooned in rags and mumbling obscenities, addicts nodding out and falling off fire hydrants. Fourteenth Street, clientele from Puerto Rico, merchandise from Taiwan. And what merchandise! In stores as garish and impermanent as sideshows at a cheap carnival, here are plastic dinner-plates and vases, plastic toys, plastic flowers and fruit, plastic statues of Jesus, plastic furniture, plastic pants and jackets-all in Day-Glo colors, naturally. And outside the stores are dark dudes in pimp-hats and shades, peddling leather belts, pink and orange wigs, and afro-combs… itinerant vendors of kebabs cooked over flaming charcoal in aluminium handcarts… crazy old men selling giant balloons.., hustlers of every description. And further on, through the perpetual fanfare of disco music and car horns, past the Banco Populare, here is Union Square, under the shadow of the Klein Sign. Klein’s, a semi-respectable old department store, was driven out of business by the local traders and has lain empty for years. But its falling apart facade still looms over the square, confirming the bankrupt status of the area. While in the square itself—over here, brother, here, my man, I got ’em, loose joints, angel dust, hash, coke. THC, smack, acid, speed, Valium, ludes. Seconal. Elavil!

NEW YORK, city of contrasts! Here we are on Fourteenth Street, walking past The New School Graduate Faculty, a clean modern building. Inside it today there is a fine museum exhibit of surreal landscape photography, but the drapes are permanently closed across the windows because, out here on the stained sidewalk, just the other side of the plate-glass, it’s Filth City, peopled by the usual cast of winos, monte dealers. shopping-bag ladies festooned in rags and mumbling obscenities, addicts nodding out and falling off fire hydrants. Fourteenth Street, clientele from Puerto Rico, merchandise from Taiwan. And what merchandise! In stores as garish and impermanent as sideshows at a cheap carnival, here are plastic dinner-plates and vases, plastic toys, plastic flowers and fruit, plastic statues of Jesus, plastic furniture, plastic pants and jackets-all in Day-Glo colors, naturally. And outside the stores are dark dudes in pimp-hats and shades, peddling leather belts, pink and orange wigs, and afro-combs… itinerant vendors of kebabs cooked over flaming charcoal in aluminium handcarts… crazy old men selling giant balloons.., hustlers of every description. And further on, through the perpetual fanfare of disco music and car horns, past the Banco Populare, here is Union Square, under the shadow of the Klein Sign. Klein’s, a semi-respectable old department store, was driven out of business by the local traders and has lain empty for years. But its falling apart facade still looms over the square, confirming the bankrupt status of the area. While in the square itself—over here, brother, here, my man, I got ’em, loose joints, angel dust, hash, coke. THC, smack, acid, speed, Valium, ludes. Seconal. Elavil!

Union Square wasn’t always like this. Michael Moorcock once told me that it acquired its name by being the last major battlefield of the American Civil War. Foolishly, I believed him. In truth there are ties here with the American labor movement; many trades unions are still headquartered in the old, dignified buildings, outside of which stand old, dignified union men, in defensive lunch-hour cliques, glaring at the panhandlers and hustlers toting pint bottles of wine in paper bags and giant, 20-watt ten-band Panasonic stereo portables blaring more disco! disco! disco!

Oddly enough we are looking for an address, here, of a writer who is known in the science fiction field for his almost elitist, civilized sensibilities. He has moved into an ex-office building that has been converted from commercial to residential status. Union Square is on the edge of “Chelsea”, which is supposed to be the new Soho, a zone where, theoretically, artists and writers are moving in and fixing up old buildings until, when renovations are complete, advertising execs and gallery owners will “discover” the area and turn it into a rich, fashionable part of town.

Theoretically, but not yet. In the meantime this turn-of-the-century, 16-storey, ex-office building is one of the brave pioneer outposts. We are admitted by a uniformed guard at the street entrance, and take the elevator to the 11th floor. Here we emerge into a corridor recently fabricated from unpainted sheets of plaster-board, now defaced with graffiti, but high-class graffiti, messages from the socially-enlightened tenants criticising the owner of the building for his alleged failure to provide services (“Mr. Ellis Sucks!” “Rent Strike Now!”) and here, we have reached a steel door provisionally painted in grubby Latex White, the kind of paint that picks up every fingermark and can’t be washed easily. There’s no bell, so one has to thump the door panels, but this is the place, all right, this is where Thomas M. Disch lives.

Mr Disch opens the door. He is extremely tall, genial and urbane, very welcoming. He ushers us in, and here, inside, it really is civilized. A thick, new carpet and a new couch and drapes and a fine old mahogany rolltop desk-and a view over Union Square, which is so far below that the dope-dealers dwindle to insignificance. It’s charming! So is Mr Disch, hospitably offering a wide variety of edible and drinkable refreshments. Not such an imaginative variety as is available from the natives in the square, but he offers them with considerably more graciousness and finesse.

New York, city of contrasts, also is city of high rents, so that even a relatively well-to-do quite-successful writer nearing forty has to resort to unlikely neighbourhoods to beat the accommodation problem. But the point is, Thomas Disch has travelled so widely and is so adept at living almost anywhere, he makes the outside environment seem immaterial. It is Disch’s nature to make himself at home by sheer willpower, never ill-at-ease or out-of-place, regardless of circumstances. Perhaps it is his tallness, perhaps it is his implacable control and elegant manners; he always seems to be both part of the environment and at the same time distanced from it, managing it with casual competence.

Similarly, in his writing: he has travelled widely, through almost every genre and technique: poetry, science fiction, nonfiction, movie scripts, mysteries, historical romances. And in each field he has made himself at home, never ill-at-ease or out-of-place, writing with the same implacable control and elegant manners.

Take, for example, his ventures into the science fiction field. He has logged quite a few years in this literary ghetto. Yet he has always remained a visitor rather than an inmate, part of the environment and at the same time distanced from it, with his own ironic perspective. This has not always gone down too well with the ghetto-dwellers themselves—the long-term, permanent-resident science fiction writers and fans. Some of them have been unhappy about an elegant aesthete like Disch “discovering” their neighbourhood and using the cheap accommodation for his own questionable ends.

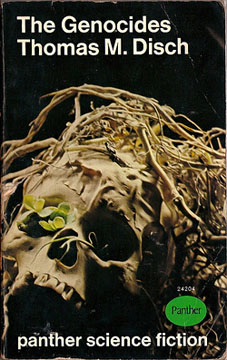

Disch’s first novel illustrates the point. Science fiction readers recognized it immediately as an aliens-invade-the-Earth story, in the tradition of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds and a thousand others. There was only one snag: in all the other novels of this type, Earth wins and the aliens are vanquished. In Disch’s novel (cheerily titled The Genocides) Earth loses and the aliens kill everybody. It almost seemed as if Disch were deliberately making fun of the traditional ways in which stories had always been told in the science fiction field.

Disch’s first novel illustrates the point. Science fiction readers recognized it immediately as an aliens-invade-the-Earth story, in the tradition of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds and a thousand others. There was only one snag: in all the other novels of this type, Earth wins and the aliens are vanquished. In Disch’s novel (cheerily titled The Genocides) Earth loses and the aliens kill everybody. It almost seemed as if Disch were deliberately making fun of the traditional ways in which stories had always been told in the science fiction field.

Naturally, he sees it differently. “To me, it was always aesthetically unsatisfying to see some giant juggernaut alien force finally take a quiet pitfall at the end of an alien-invasion novel. It seemed to me to be perfectly natural to say, let’s be honest, the real interest in this kind of story is to see some devastating cataclysm wipe mankind out. There’s a grandeur in that idea that all the other people threw away, and trivialized. My point was simply to write a book where you don’t spoil that beauty and pleasure at the end.”

To the science fiction community, Disch’s ideas about “beauty and pleasure” seemed a bit depressing, and they accused him, and have continued to accuse him, of being a pessimistic author. He responds:

“What sort of criticism is it to say that a writer is pessimistic? One can name any number of admirable writers who indeed were pessimistic and whose writing one cherishes. It’s mindless to offer that as a criticism. Usually all it means is that I am stating a moral position that is uncongenial to the person reading the story. It means that I have a view of existence which raises serious questions that they’re not prepared to discuss; such as the fact that man is mortal, or that love dies. I think the very fact that my imagination goes a greater distance than they’re prepared to travel suggests that the limited view of life is on their part rather than on mine.”

Comments like this lead, in turn, to other criticisms—for instance, that Disch is setting himself up as an intellectual.

“Oh, but I’ve always taken it for granted that I’m an intellectual,” he replies ingenuously. “I don’t think of it as being a matter of setting myself up.

“My purpose in writing is never to establish myself as a member of a club. I don’t feel hostile to my audience, indeed I’m fond of it, but to write other than what delights me would be to condescend to my audience, and I think that would be reprehensible. I think any writer who reins in his muse for the sake of some supposed lack of intelligence or sophistication on the part of his readers is… well, that’s deplorable behaviour.”

So Disch has consistently written at a level which pleases himself, and has consistently been misunderstood by science fiction readers as a result. His novel 334, a gloomy vision of America in the future, was if anything less well-received by such readers than The Genocides, and was condemned as being even more depressing—even nihilistic.

“Well, nihilism is a pejorative that people throw out by way of dismissing an outlook,” he replies. “It was one of Agnew’s words. Agnew loved it because it means that someone believes in nothing and, of course, we know we don’t approve of people like that. But it also throws up the problem of what do you believe in. God? Is he a living god? Have you seen him? Do you talk to him? If someone calls me a nihilist I want the transcripts of his conversation with Jesus, till I’m convinced that we’re not brothers under the skin.”

And about the book 334 itself:

I think what distressed some people is that it presents a world in which the macroproblems of life, such as death and taxes, are considered to be unsolveable, and the welfare system is not seen as some totalitarian monster that must call forth a revolt of the oppressed masses. The radical solution shouldn’t be easier to achieve in fiction than in real life. Almost all science fiction presents worlds in which social reform can be accomplished by the hero of the tale in some symbolic act of rebellion, but that’s not what the world is like, so there’s no reason the future should be like that.”

Is this an argument that all fiction should be relentlessly tied to present-day realities?

“I’m not saying that every writer has to be a realist, but in terms of the ethical sensibility brought to bear in a work of imagination, there has to be some complex moral understanding of the world. In the art that I like, I require irony, for instance, or simply some sense that the writer isn’t telling egregious lies about the lives we lead.”

I reply that it isn’t necessarily a bad thing if readers look for some simplification of the eternal problems of real life, or at least a little escape from them now and again.

“People who want that are certainly supplied with it often enough. Of course there’s no reason that artistry can’t he brought to bear upon such morally simplistic material, but it remains morally simplistic, and to me it will always be a lesser pleasure than the same artistry brought to bear on morally complex material. The escapist reader wants a book that ends with a triumph of the hero and not with an ambiguous accommodation; I suppose I’m inclined to think that you can’t have it that way. I don’t know people who have moral triumphs in their lives. I just know people who lead more, or less, good lives.

“A literature that doesn’t try to mirror these realities of human existence, as honestly and as thoroughly and as passionately as it can, is being smaller than life. Who needs it?”

TOM DISCH was born in Iowa in 1940 and grew up in Minnesota, first in Minneapolis-St Paul (“Always my growing-up image of the big city”) and then in a variety of small towns. “I went to a two-room country school for half of fourth grade… finished fourth grade in the next town we moved to in Fairmont, Minnesota, which is in the corn belt…”

At the age of nine he had already started writing: “I filled up nickel tablets with science fiction plots derived from one of Isaac Asimov’s robot mystery stories. If we could find those nickel tablets I’m certain that the resemblance would be astonishing. But I think my stories were livelier even then.” He laughs happily.

“I remember a moment in tenth grade in high school, talking to my English teacher—I was always the pet of my English teachers and made them my confidants—and I envisioned two alternatives. One of them would have kept me in the twin cities on the paths of righteousness and duty (I can’t remember what that would have been, exactly), the other was to come to New York and be an Artist.

“My first job after high school, after taking some kind of test at the state employment center, was with U.S. Steel as a trainee structural steel draftsman. I stuck it out through that summer till I’d saved enough money to come to New York. Then in New York I got the lowest type of clerical jobs.

“I wanted to get into Cooper Union, to the architectural school. My idea was to be Frank Lloyd Wright. Cooper Union did accept me. Even though the tuition was free, I still had to work as well, and in the end l just collapsed from overwork and possibly from lack of real ambition to be an architect. Architects have to study a lot of dull things for a very long time and I probably wasn’t up to it.”

Disch returned to university later, but: “The only purpose I had in mind, then, for any degree I might have acquired, would have been to become an academic, and I thought it would be better to be a writer, so as soon as I sold my first story I dropped out of college.”

Supposedly, a major factor that influences people to read a lot of science fiction, and then write it, is a sense of childhood alienation. I ask Disch if he had that experience. He is skeptical:

“All young people are prone to feel alienated, because that’s their situation in life. Very often they haven’t found a career, don’t have a social circle they feel is theirs, and they feel sorry for themselves, accordingly. Certainly it’s something real that happens to you, but with luck you work your way out of it and soon your social calendar will be filled and you won’t complain about alienation any more. You’ll get married. Very few married men with children complain about alienation.”

Disch himself seems unusually gregarious, for a writer, and many of his projects have been written in collaboration with various other authors. His first collaborator was John Sladek. “We started writing together in New York in the summer of 1965, just short japes at first, and then two novels. One was

gothic which is best forgotten. The other was Black Alice.” (A contemporary mystery/suspense novel.)

“My experience of collaborating with other writers is just mutual delight. One person has a good idea and the other says, that’s great, and then what-if… It builds. Writing in collaboration with a person whose work you admire, miraculously sections of the book are done for you, it’s like having dreamed that you wrote something, it eliminates all the real work of writing.

“I’ve planned other collaborations. I’ve worked with composers on a small musical and an opera, and I just like the process of it. I would like to write for movies. Other writers complain about the horrors of dealing with directors, but if it’s a director one admires I would think that it would be exciting and if it’s not a director you admire then you shouldn’t be doing it. It would be difficult to share my own most earnest novels, but for comic writing, for instance, I should think it would be so much more exciting to write for Saturday Night Live than just to write humorous pieces for magazines however great your inspiration.”

The range of people whom Disch has worked with reflects the range of different forms of writing that he is interested in. “Part of my notion of a proper ambition is that one should excel at a wide range of tasks. I want to write opera libretti; want to write every kind of novel and story; I’ve written a lot of poetry and I will continue to do so. I foresee a pattern of alternating between science fiction novels, and novels of historical or contemporary-realistic character.”

I ask if he isn’t worried that this will give him too diffuse an image in the minds of publishers, who are generally happier if a writer can be given a single genre-label.

“Publishers do feel more comfortable with you if you are, in a sense, at their mercy. They prefer you to be limited as a writer. If you’re a science fiction writer who begins to write a kind of science fiction that isn’t to the taste of a publisher whom you’ve been working with, they will in effect say, stick to what you know best, go back and write the kind of book that has made you successful. If you are a genre writer then genre editors can dictate to you the terms of the genre. In the long term they’re asking for the death of the imagination, and a dreary sameness of invention, plots, and characters is the result.”

Since Disch has managed to avoid being typecast in this way. I ask him which matters more to him—success and recognition in the science fiction field, or outside of it.

“I would suppose that any science fiction writer would rather be successful in the big world than in the small world. The rewards are greater. Not simply financially, but the rewards of public acclaim. If the approval of your peers means anything, then the approval of more of your peers must mean more. And not all of the palates that you want to tickle, the critics you hope to please, are within the science fiction field. In fact the big judgement seat is outside of it.”

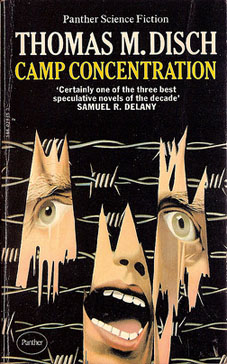

I ask if Disch’s best-known novel, Camp Concentration, was an attempt to achieve recognition outside of the science fiction field.

I ask if Disch’s best-known novel, Camp Concentration, was an attempt to achieve recognition outside of the science fiction field.

“Camp Concentration was a science fiction novel, I think it was probably not strong enough to stand on its own outside the genre. Not as a work of literature. It might have been marketed as a middle-brow suspense novel—some science fiction is smuggled out to the real world in that disguise—but I think the audience outside of science fiction is even more resentful of intellectual showing-off, while within science fiction there’s been a kind of tradition of it. Witness something like Bester’s The Demolished Man, which was in its day proclaimed to be pyrotechnical. Pyrotechnics are part of the science fiction aesthetic, and that’s what Camp Concentration was aiming at.

“In America the novel didn’t receive very much attention and it became the focus of resentment for some of the fuddy-duddy elements in science fiction to carp about. I never had enough success with the book to make me seem a threat and I’m not much of a self-promoter, so the book just vanished in the way that some books do. And that’s not entirely a bad thing. The kind of success that generates a lot of attention can be unsettling to the ego, and the people who have that kind of success are often encouraged to repeat it. It would have been a very bad thing if I had bowed to pressure to write another book like Camp Concentration, which was the expectation, to a degree, even in myself. For a while I wanted to write things that were even more full of anguish, and even more serious.”

Camp Concentration is, as Disch says, very serious and full of anguish. It is the diary of a character who is locked up and given a drug to heighten his intelligence; an unfortunate side-effect of the drug is that it induces death within a matter of months. The book thus presented a double challenge to Disch: he had to write the diary of a man who knows he is going to die, and he had to write the diary of a man whose intelligence is steadily increasing to superhuman levels. In a way it was a self-indulgence—a conscious piece of self-analysis—in that Disch himself is aware of his intelligence to the extent that it is something of a fetish.

While he was working on Camp Concentration, he confided to Michael Moorcock, (as Moorcock tells it), “I’m writing a book about what everyone wants most.”

To which Moorcock replied: “Really? Is it about elephants?”

“Elephants? No, it’s about becoming more intelligent.”

“Oh,” said Moorcock, “what I’ve always wanted most is to be an elephant.”

Talking to Tom Disch, I recount this anecdote, if only to check on its accuracy. Disch laughs and comments, “Well, I guess Mike Moorcock and I have both realized our secret dreams.”

© Charles Platt, 1980. Old paperback covers taken from Jovike’s great Flickr set.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Revenant volumes: Bob Haberfield, New Worlds and others

thanks for this!

i found out on Saturday about Disch’s death and have been in a complete funk for days…

each day that goes by i’m more and more surprised at the outpouring of respect and love from that comes from “regular people” and the blogosphere, and am dismayed at the lack of anything from the mainstream.

Disch probably already had that figured out… ;-)

Hi Ray. Thanks are due to Charles Platt who I hope doesn’t mind me posting this. (Both editions of the book are out of print.)

Formal obits in the news media seem to be coming along at last but it often takes them a while to rouse themselves with writers who are highly-regarded but whose names mean nothing to journalists.

Unfortunately, I haven’t read anything by Mr. Disch, but the fact that someone realtively young, and successful in his career as a writer (i believe), takes his own life, as well as many others who did that, including Barney Bubbles and Ian Curtis, makes me sad yes, but I tell you, people, that I kind of understand what motivated them, although I really wish I didn’t!

R.I.P.

Sorry to come so late to the party, but I’ve only recently become acquainted with your excellent weblog.

That said, I had long been a fan of Tom Disch (having loved Camp Concentration, The Genocides, 334, and even having obtained a signed paperback copy of Fun With Your New Head. Though I knew of his death three or so years ago, I still miss Tom’s unique view of life.

I’m writing because I thought that in the event that you did not know it, Tom was also quite a capable poet as well as genre writer and intellectual. The ‘smoking gun’ or evidence of his literary crimes can be found here, as preserved by the American poet, Dana Gioia:

http://www.danagioia.net/essays/edisch.htm

Dana also did a quite capable memorial of Tom, which may be found here:

http://www.danagioia.net/essays/edisch2.htm

If I were in the habit of dropping names, I would perhaps mention that I refer to Mr. Gioia by his Christian name because I was a friend of his when we were both in high school. But as I am not in the habit, I guess that I just won’t.

Thanks, Bernard. I did see the poetry Disch was writing up to the last few days of his life, he received a fair amount of attention for it at the time. His versatility was most impressive, as I note above, he was always more than merely an sf writer.