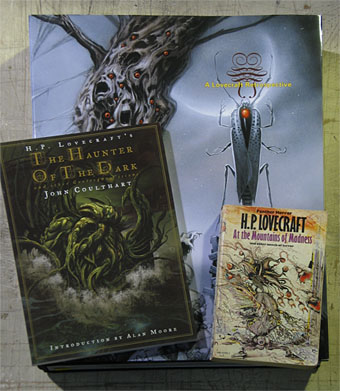

So it arrived at last, yesterday in fact, the colossal volume that is A Lovecraft Retrospective: Artists Inspired by HP Lovecraft from Centipede Press. Calling this a book is like calling the Great Pyramid of Cheops a pile of stones, technically accurate but the words somewhat fail to convey the existential reality. This is the heaviest book I’ve ever come across, 400 pages of heavy-duty art paper at BIG size. (Amazon gives the dimensions as 16.1 x 12.6 x 2.3 inches or 409 x 320 x 580 mm.) The photo above shows the scale beside an old Mountains of Madness paperback (Ian Miller‘s cover art appears in full in the new book) and my own Haunter of the Dark collection. The cover art is by Michael Whelan, a detail from his wonderful 1981 HPL panoramas.

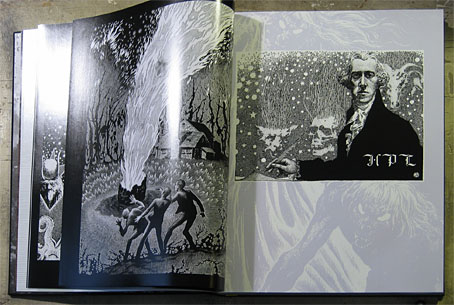

The Virgil Finlay section showing The Colour Out of Space and his definitive Lovecraft portrait.

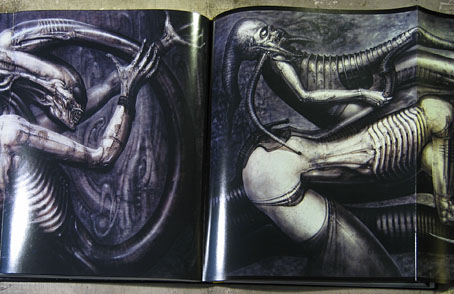

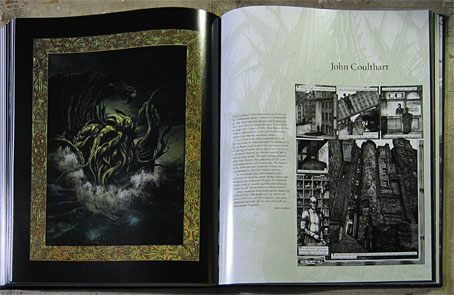

The range of contributors past and present includes JK Potter, HR Giger, Raymond Bayless, Ian Miller, Virgil Finlay, Lee Brown Coye, Hannes Bok, Rowena Morrill, Bob Eggleton, Allen Koszowski, Mike Mignola, Howard V. Brown, Michael Whelan, Tim White, Frank Frazetta, John Holmes, Harry O. Morris, Murray Tinkelman, Gabriel, Don Punchatz, Helmut Wenske, John Stewart, Thomas Ligotti and John Jude Palencar. The introduction is by Harlan Ellison and there’s an afterword by Thomas Ligotti. Many pages fold out to reveal spreads like the Giger ones below. Print quality is exceptional, of course, but then ladling the superlatives is pointless when it’s obvious this is a sui generis masterpiece of Lovecraftian art. Naturally I’m very happy indeed to be a part of it.

A pair of Necronoms by HR Giger.

I don’t have to photograph too much since other people have been doing the same with their copies. Matt Staggs has more pictures of the contents here and Jeff VanderMeer has made the book a feature of his latest art column for io9. Jeff talks to Centipede Press’s Jerad Walters about the book’s production and notes on his own blog what an important, landmark volume this is. Having done my fair share of book production I can imagine what an undertaking it was. Jerad should be very pleased he’s been able to put together a book which bests the productions of multinational publishers with their armies of staff. And we might even ask why it’s left to a small independent publisher to produce something of this quality at all.

Jeff asked me a few questions for his io9 piece which I’m reproducing in full here.

• Everyone knows what Lovecraft means to fantasy and horror. What do you think he meant for the idea of “cosmic SF”?

JC: The young Lovecraft was a keen astronomer who became acquainted at an early age with a sense of cosmic scale, the vastness of the universe and so on. That combined with a natural pessimism and his later atheism gave him a strong sense of human insignificance in the face of cosmic enormity. “We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity,” as he says at the opening of The Call of Cthulhu.

His problem as a writer was that most Western supernatural fiction up to that point had some kind of Christian dimension to it, even if this wasn’t directly stated. That was obviously a problem for an atheist writing a form of fiction which needed something malevolent at its core. His solution was to replace the Devil and the Christian idea of evil with vast extra-dimensional entities which disturb or threaten us either because we mean as much to them as microbes do to human beings or (in the case of Cthulhu) they’re eager to take reclaim the earth for their own destructive ends. All of Lovecraft’s best fiction tends to be sf used for horror purposes; he’s telling the same old tales about what might lurk in the dark beyond the campfire, only the campfire is now the planet Earth and the dark is the interstellar void.

• What personally resonates with you re Lovecraft?

JC: I think initially it was that skilful blend of sf and horror. When I was a kid I always enjoyed reading ghosts stories as much as science fiction. The first story of Lovecraft’s I read was The Colour Out of Space, a tale of a meteorite which crashes near a farm and whose insidious infection slowly affects the farm and the surrounding countryside. That’s an incredibly chilling story—one of his very best—and yet there’s nothing supernatural in it. In his best work he builds a sinister atmosphere to a remarkable degree, something he’d learned by studying previous writers. Other writers of the period and even more recent writers often seem lightweight in comparison. Later on I got drawn into the tangled web of the Cthulhu Mythos which is a compelling attraction for new readers.

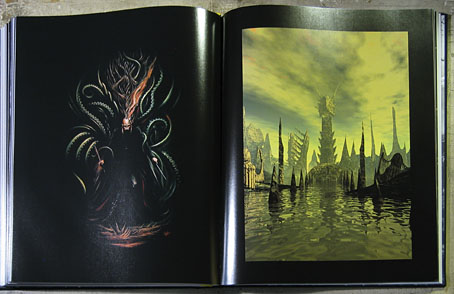

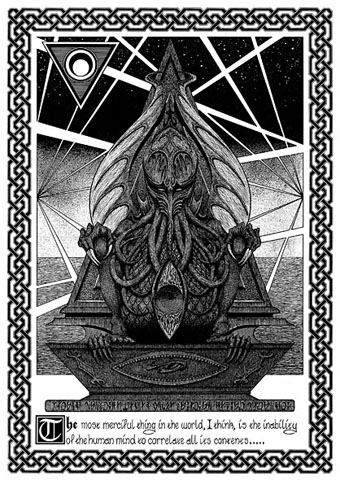

The Call of Cthulhu (1988).

• How did you put your personal stamp on your Lovecraft-influenced art?

JC: I wanted to take Lovecraft’s fiction seriously on its own terms, something which—in the comics world especially—wasn’t happening very often. When I started illustrating his work in the 1980s there was little apart from the Lovecraft special issue of Heavy Metal from 1979 which had attempted that. I tried to match his dense writing style with an equally dense and detailed drawing style and tried to make things look solid and historically accurate. I’ve always been interested in architecture and Lovecraft’s concept of alien architecture continues to fascinate; I explored that in a small way last year in a picture commissioned for a Swiss exhibition (below).

Detail from “Mirage in time—image of long-vanish’d pre-human city” (2007).

• Lovecraft clearly tapped into something hidden or buried in readers. What was it, as far as you’re concerned?

I’ve thought for years that the invented mythology is one of the things which really hits people, even if they don’t read many of the stories. It was this which powered the Call of Cthulhu role-playing games. People don’t have to be religious to feel the draw of a mythology or invented taxonomy, you can see that in other areas whether it’s Star Trek, Star Wars or Harry Potter. That’s probably the juvenile attraction; the more sophisticated one would be the attraction for people such as Michel Houellebecq who see Lovecraft as a kind of pulp Kafka or Camus. You can be drawn into his writing by something trivial like Hello Cthulhu then journey deeper to discover a great imagination at work and even a philosophical viewpoint; anything that works on all those levels we need to label “art”.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

• The fantastic art archive

• The illustrators archive

• The Lovecraft archive

Congrats!!!

Thanks Thom. What I need now is one of those power lifters from Aliens to help me move it around.

I can’t believe I’m only hearing of this amazing book now. Great interview, too.