Compound Fracture (1990).

No title (1992).

Examinations (2004).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Compound Fracture (1990).

No title (1992).

Examinations (2004).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Frank Miller and 300‘s Assault on the Gay Past.

No sex please, we’re Spartans.

Ry Cooder rules. New album out today sees Ry accompanied by Mike & Pete Seeger, Roland White, Van Dyke Parks, Paddy Moloney, Flaco Jiménez, Stefon Harris, Joachim Cooder and Jon Hassell. Cover drawing and interior illustrations by Vincent Valdez.

On My Name Is Buddy, Ry Cooder revisits, in a new set of original material, the sound and feeling of the “dust bowl songs” he first explored more than three decades ago on such groundbreaking albums as his self-titled 1970 debut and 1971’s Into The Purple Valley. In fact, he’s joined by old friends like pianist Van Dyke Parks and drummer Jim Keltner who were with him at the start of his extraordinary, ultimately globe-spanning musical odyssey, which has yielded him six Grammy Awards to date, several more nominations, and perennial acclaim. My Name Is Buddy is also a journey, a phantasmagorical rendering in music, words and pictures of the travels of three unlikely cohorts—Buddy Red Cat, Lefty Mouse and Reverend Tom Toad—as they meander through the west “in the days of labor, big bosses, farm failures, strikes, company cops, sundown towns, hobos and trains…the America of yesteryear.” For this allegorical tale, Cooder marshals all his remarkable skills as a producer, arranger, songwriter, soundtrack composer and musicologist. (The Christian Science Monitor recently dubbed him “a modern-day Alan Lomax.”) My Name Is Buddy recalls Woody Guthrie’s Bound for Glory—that is, if it had been enacted by the articulate animal characters of Walt Kelly’s classic comic Pogo. Cooder conjures up the dark shadows of an earlier time to wryly comment on the political and social issues of the present. As back-story to his songs, Cooder has written short stories for each one and they’re accompanied by evocative illustrations from noted San Antonio-based painter and muralist Vincent Valdez, all of which are included in a specially designed package.

Free PDF magazines.

Lots of them, aggregated for your downloading pleasure. Damn. Via.

The riddle of the rocks by Jonathan Jones

It was the art movement that shocked the world. It was sexy, weird and dangerous—and it’s still hugely influential today. Jonathan Jones travels to the coast of Spain to explore the landscape that inspired Salvador Dalí, the greatest surrealist of them all.

The Guardian, Monday March 5, 2007

I AM SCRAMBLING over the rocks that dominate the coastline of Cadaqués in north-east Spain. They look like crumbling chunks of bread floating on a soup of seawater. Surreal is a word we throw about easily today, almost a century after it was coined by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Yet if there is anywhere on earth you can still hope to put a precise and historical meaning on the “surreal” and “surrealism”, it is among these rocks. To scramble over them is to enter a world of distorted scale inhabited by tiny monsters. Armoured invertebrates crawl about on barely submerged formations. I reach into the water for a shell and the orange pincers of a hermit crab flick my fingers away.

The entire history of surrealism—from the collages of Max Ernst to Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone—can be read in these igneous formations, just as surely as they unfold the geological history of Catalonia.

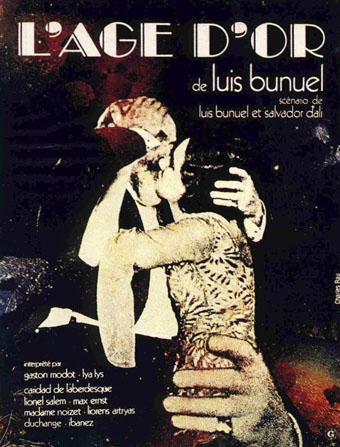

I sit down on a jagged ridge. What if I fell? Would they find a skeleton looking just like the bones of the four dead bishops in L’Age d’Or, the surrealist film Luis Buñuel shot here in 1930?

Buñuel had been shown these rocks by his college friend Dalí years earlier. It was here they had scripted their infamous film Un Chien Andalou. Dalí came from Figueras, on the Ampurdán plain beyond the mountains that enclose Cadaqués, and spent his childhood summers here, exploring the rock pools and being cruel to the sea creatures. In most people’s eyes, this is a beautiful Mediterranean setting. It certainly looked lovely to Dalí’s close friend, the poet Federico García Lorca, when Dalí brought him here in the 1920s: in his Ode to Salvador Dalí, Lorca lyrically praises the moon reflected in the calm, wide bay…

Continues here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The persistence of DNA

• Salvador Dalí’s apocalyptic happening

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

• Dalí Atomicus

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie