The cult writer is about to publish his first novel for nine years. But the best-selling author of V and Gravity’s Rainbow remains an enigma to his millions of fans. By Louise Jury

The cult writer is about to publish his first novel for nine years. But the best-selling author of V and Gravity’s Rainbow remains an enigma to his millions of fans. By Louise Jury

August 17, 2006

The Independent

He is so elusive a writer that he makes Harper Lee appear a socialite. He gives no interviews and shuns all photo opportunities. Thomas Pynchon, cult figure of American prose, is a nightmare for his publicists.

But the mystery surrounding the 69-year-old author will serve only to increase the clamour when his next novel, Against the Day, is published in December simultaneously in the UK and the US. It will be his first novel in nine years and only his sixth—plus a collection of early fiction—since his astonishing debut with V in 1963.

Finally announcing the date yesterday, Dan Franklin of Jonathan Cape, his British publisher, said that to have a new work was “incredibly exciting”. He added: “Against the Day is an epic that is awesome in its scope and imagination.”

Yet such is the secrecy surrounding this literary great that it is not even clear when reviewers will get to see the £25 tome. For clues as to its subject matter, we are in the hands of the author himself for now.

Pynchon outlined a novel yesterday that was vast in ambition with a veritable dictionary of national biography as the cast, down to cameo appearances by the scientist Nikola Tesla, Bela Lugosi and Groucho Marx.

But the author’s description was so over the top that he seemed almost to be irreverently mocking the conventions of publicity even while apparently taking part.

The novel, he said, spanned the period between the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 and the years just after the First World War but embraces a whole raft of countries and other events.

“With a worldwide disaster looming just a few years ahead, it is a time of unrestrained corporate greed, false religiosity, moronic fecklessness, and evil intent in high places.” Parrying the interpretations of future critics, he continued: “No reference to the present day is intended or should be inferred.”

Meanwhile, he indicated that features well-known to his fans, such as “for the most part stupid songs” would be included and “contrary-to-the-fact occurrences occur”. “If it is not the world, it is what the world might be with a minor adjustment or two. According to some, this is one of the main purposes of fiction,” he said.

It was a teasing statement surely designed to entice the cult readership which saw his last work, Mason & Dixon, sell out an initial 175,000 print run in the US in around six weeks. Then, despite being criticised by some as incomprehensible and stretching to an intimidating 773 pages, the book was requisite reading for the literati in his home nation. In the words of his American publicist: “Reading Pynchon makes people feel smart.”

And readers clearly like the mystery of his identity. What is known is that Thomas Pynchon was born on 8 May, 1937, on Long Island, New York. A gifted student, he studied engineering physics at Cornell University, but left for a spell in the American navy. It was a period when he was photographed in a pose which is much reproduced in the absence of any others. The navy has also provided material for his books.

But when he returned to university, he switched to studying English in a department where the author Vladimir Nabokov was one of his professors. After graduating in 1959, he worked briefly as a technical writer before turning to fiction.

V, an absurdist comedy which introduced readers to Pynchon’s dense style, was published to acclaim as the best first novel of the year in 1963.

Immediately added to the list of great new prose modernists, in the mould of Kurt Vonnegut and Joseph Heller, Pynchon followed V with The Crying of Lot 49 in 1966, the shortest and most accessible of his works, which he later dismissed. Then in 1973 came Gravity’s Rainbow, a labyrinthine story where fact cannot be separated from fantasy, set in the dying days of the Second World War. It won the prestigious National Book Award in the United States and was unanimously recommended for the Pulitzer Prize by its fiction jury. While the Pulitzer board rejected the recommendation and condemned the novel as “unreadable” and “overwritten”, it remains probably his most celebrated novel.

But it was followed by a long wait of 11 years until Slow Learner, a collection of his early short stories—with an introduction by Pynchon himself which offered a rare and intriguing insight into his thinking. In a masterclass to other writers, he warned against approaching a story with a “theme, symbol, or other abstract unifying agent” and making the characters conform to it. He argued that writing should have “some grounding in human reality”. To many, the introduction remains the biggest—arguably, the only—clue to Pynchon’s art.

In 1990 came Vineland, another novel packed with eccentric characters and infused with a strong strain of paranoia across different time frames. Then in 1997 came Mason & Dixon, which was a vast epic based on the true story of British surveyors establishing the boundary that lay at the heart of the American Civil War.

This was, the New York Times reviewer said, “the old Pynchon, the true Pynchon, the best Pynchon of all. Mason & Dixon is a groundbreaking book, a book of heart and fire and genius, and there is nothing quite like it in our literature, except maybe V and Gravity’s Rainbow“.

Such hyperbole makes clear the burden of expectation which rests on the new work.

But if Against the Day, to be published on 5 December, is the subject of fevered speculation over the coming months, it will be no more than is routinely applied to the details of the author’s life. Pynchon is said to be married to his literary agent with whom he has a son. Although some believed he lived in California, the location of his fourth novel, Vineland, and a photograph of the author taken from behind on a Manhattan street and published in New York magazine a decade ago, suggested that he was instead resident in the Big Apple.

Despite his aversion to publicity, which is on a par with that of Catcher in the Rye author JD Salinger, Pynchon has not avoided the modern world entirely. In 1968, he signed a newspaper pledge with other writers and editors not to pay a proposed tax to fund the Vietnam war.

He has written a number of articles and reviews in the American media, including an article offering support to Salman Rushdie after the fatwa was pronounced against him.

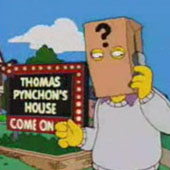

And he has even “appeared” in cameo—and, obviously, animated—appearances in The Simpsons. Mocking his own reclusiveness, he first appeared in the show with a paper bag over his head to proffer a supportive quote for a novel written by Marge Simpson.

Regarded as hugely influential on a whole generation of innovative younger writers including the American David Foster Wallace and Britain’s David Mitchell, Pynchon remains one of the grand old men of American fiction.

But whether his new book will become a bestseller remains to be seen. Rodney Troubridge, a fiction expert at Waterstone’s bookstores, said: “He’s one of the heavyweights, one of the top six heavyweight American writers—and they do have heavyweight writers. It’s nice to have such a book after nine years. People will be interested.”

What worries Rodney Troubridge is the price tag, particularly when, as with all cult authors, so many of the potential readership are students.

“At £25, it’s pretty steep. I can see it doing better in paperbacks for real punters, the people who love him.”

So despite the fame, the mystery and the awards, the stark truth is that in Britain, at least, he is not a big seller. But, as Mr Troubridge conceded: “He is a name.” A name, of course, without a face.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Thomas Pynchon—A Journey into the Mind of [P.]

• A literary event: new Thomas Pynchon