Tom Phillips has long been one of my favourite contemporary artists and he’d certainly be my candidate for one of the world’s greatest living artists even though the world at large stubbornly refuses to agree with this opinion. Phillips’ problem (if we have to look for problems) would seem to be an excess of talent in an art world that doesn’t actually like people to be too talented at all (unless they’re dead geniuses like Picasso) and a lack of the vaunting ego that propels others into the spotlight.

Phillips is predominantly a painter but a restlessly experimental one. On my journey through the London galleries in May I visited the National Portrait Gallery, a rather dull place mostly filled with pictures of the rich and famous by the rich and famous. There were two Tom Phillips works on display in different rooms, inadvertently showing his artistic range: one, a fairly standard (if very finely detailed) portrait of Iris Murdoch, the other a computer screen showing a portrait of Susan Adele Greenfield which manifested as an endlessly-changing series of 169 processed drawings and video stills. One work was static and traditional, the other fluid, contemporary and unlike anything else in the building.

But Phillips isn’t only a painter, of course, he produces sculptural works, books such as The Postcard Century (presenting samples of his voluminous postcard collection) and many others, is the author of an experimental opera, IRMA, and co-author (with writer WH Mallock) of the extraordinary A Humument where “the artist plays Pygmalion with WH Mallock’s A Human Document (1892)” by drawing and painting over every single page of a Victorian novel leaving certain words visible, thereby creating a completely new text. A detail of one of his paintings, After Raphael, was used by ex-art pupil Brian Eno as the cover for Another Green World. He also provided the cover art for Eno’s Thursday Afternoon. Eno has said:

It’s a sign of the awfulness of the English art world that he isn’t better known. Tom has committed the worst of all crimes in England. He’s risen above his station. You can sell chemical weapons to doubtful regimes and still get a knighthood, but don’t be too clever, don’t go rising above your station.

The smart thing in the art world is to have one good idea and never have another. It’s the same in pop—once you’ve got your brand identity, carry on doing that for the rest of your days and you’ll make a lot of money. Because Tom’s lifetime project ranges over books, music and painting, it looks diffuse, but he is a most coherent artist. I like his work more and more.

Phillips produced the cover for one of King Crimson’s best albums, Starless and Bible Black, adorning it with a display of his habitual stencil lettering and an enigmatic phrase from A Humument, “This night wounds time.” His obsession with Dante has led him to translate The Inferno in order to produce an illustrated edition and in the late Eighties he collaborated with Peter Greenaway on A TV Dante, a marvellous adaptation for television screened in the UK by Channel 4.

Of all his works, one of my favourites remains his ongoing 20 Sites n Years.

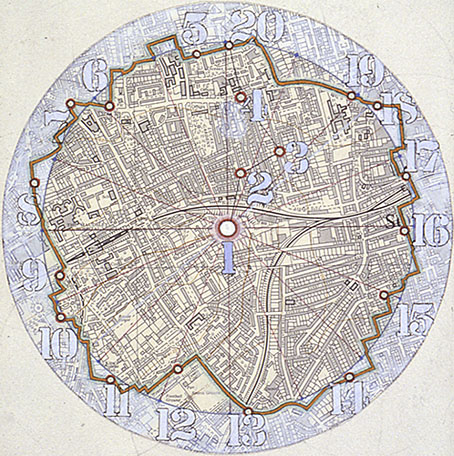

Every year on or around the same day (24th May–2nd June) at the same time of day and from the same position a photograph is taken at each of the twenty locations on this map (above) which is based on a circle of half a mile radius drawn around the place (Site 1: 102 Grove Park SE15) where the project was devised. It is hoped that this process will be carried on into the future and beyond the deviser’s death for as long as the possibility of continuing and the will to undertake the task persist.

The intention is that photographs (35 mm transparencies) be taken at twenty locations each year between May 24 and June 2. The locations are situated on what is (in 1973) the nearest walkable route to a perfect circle a half a mile in radius from the point in the home of Artist 1 (102 Grove Park, London SE5) where the project was devised and where these instructions were written. The circuit is divided into sixteen equal sections in each of which there is a site selected by Artist 1. Four other locations mark the route from the centre to the circumference: these are the former studio of Artist 1, his current home and studio, and the art school where he studied. The project book notes the times of the original photographs of 1973 and these should be adhered to as closely as possible (though all photos need not necessarily be taken on the same day) Artist 1 intends that the pictures should be taken by his family and their descendants, if they are willing, and that the work should thus go on indefinitely: the services of their friends may be enrolled or even from time to time that of professional photographers. Continuity is the most important factor.

The result is an evolving pictorial history of a very mundane area of south London; as the pictures accumulate the city begins to flex and change before our eyes like a living being. By turning his attention to ordinary streets rather than grand buildings Phillips has shown us the degree to which our living space is in a continual state of flux as well as revealing curious psychogeographic resonances, like the tank that goes down a road in 1982 when the Falklands War was in progress.

As so often in 20 Sites no pattern or plan is discernible in the changes made to things or their positioning or even their existence. A bench will move here and there, and will disappear altogether to come back again after a while: if indeed 20 Sites is seen as a microcosm of the nation as a whole then an awful lot of people, especially those working for the municipality, are involved in totally random and arbitrary activity. They seem to cancel out each other’s work in a long dance of job protection. It is difficult otherwise (apart from the signals-to-aliens theory) to account for the preparation of a flower bed in 1973 whose display reaches its peak in 1975, goes to seed in 1976, is erased in 1977 to remain more and more vestigially visible until in 1987, when, as if to mark the tenth anniversary of its abandonment, a Christmas tree is planted (by chance or artistry) dead centre of its virtually invisible circle. It made little progress in 1989 and still looks sketchy in 1992.

Every time I look at these pictures I wish I had the discipline to attempt something similar since one could easily clone the project for other cities. I suspect it’s only a matter of time before someone attempts this elsewhere (assuming they haven’t already) although whether they can sustain the activity the way Phillips has done remains to be seen. His specification that the work should be continued after his death is already assured since his son has been an active participant for some years. I’m curious as to how they’ll proceed in the future now that film cameras are becoming an endangered species (Phillips specifies the type of camera and film stock to be used).

Thames & Hudson publish three books of Phillip’s work, the essential Works and Texts (which includes details of 20 Sites n Years), The Postcard Century and A Humument (now in its fourth edition). If there was any justice in the world, Tate Modern would honour him with a major retrospective. But there isn’t so they won’t.

May 2012 sees a new edition of A Humument and exhibitions by TP in London.