Heptu Bidding Farewell to the City of Obb (1909). Another of those paintings that provide a link between 19th-century art and 20th-century fantasy illustration.

Scotland isn’t a nation commonly associated with Symbolist painting, or with what The Studio magazine called “mystic subjects” when writing about John Duncan’s painting of Heptu on her hippogriff. There were a handful of Scottish artists in the late 1800s whose work suits the description, mostly the members of the Glasgow School, although some of these would be considered marginal cases compared to their Continental contemporaries. In the Anglophone countries Symbolist art is so thin on the ground that Michael Gibson in Symbolism (1995) puts Great Britain and the United States into a single chapter, and even there many of the artists he highlights—people such as Thomas Cole and the Pre-Raphaelites—are more like precursors, being too early to be considered an active part of a movement that only established itself in the 1880s.

The Legend of Orpheus (1895).

John Duncan does fit the bill, however, more so than I would have expected until I started looking at his paintings. Duncan’s career oscillated between Dundee and Edinburgh so he avoided the Arts and Crafts tendencies of the Glasgow School. His work is closer to French artists like Alexandre Séon, especially in the sculptural treatment of his figures. Familiar subjects and motifs abound: the riddle of the Sphinx, peacocks, Wagner, sorcery, and a variety of myths and legends, from Scotland to ancient Greece. The ink drawings here are from The Evergreen, A Northern Seasonal, a small art and literature magazine published in Edinburgh that managed four issues from 1895 to 1896. In Duncan’s later work he avoided the upheavals of Modernism by keeping to safe religious subjects. If the date is accurate for that Sphinx it must have seemed very old-fashioned in 1934.

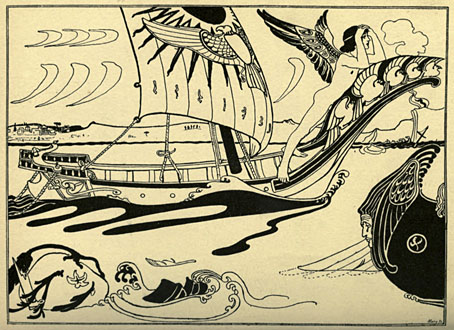

Out-Faring (1895).

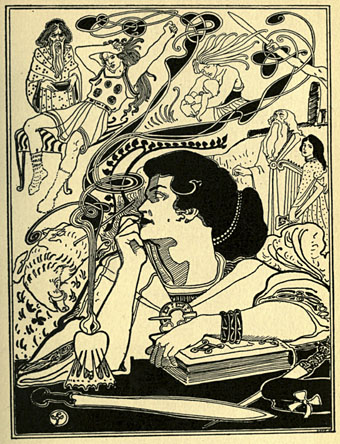

Anima Celtica (1895).

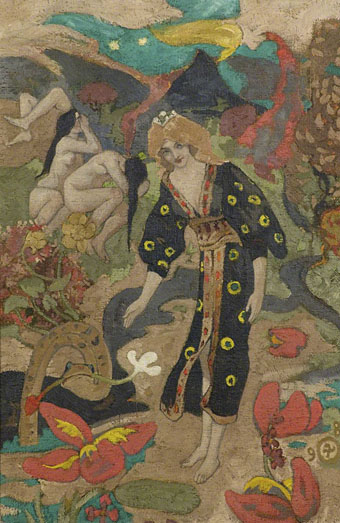

A Sorceress (1898).

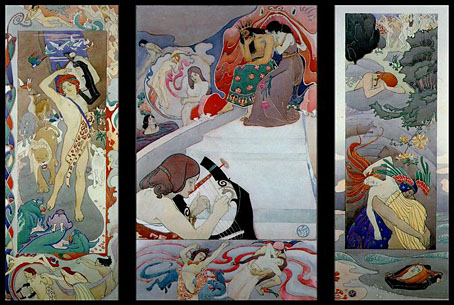

Ivory, Apes and Peacocks (The Queen of Sheba) (1909–1920).

Unicorns (1933).

The Challenge (1934).

Masque of Love.

The Fomors (or The Powers of Evil Abroad in the World).

Force and Reason.

Happiness.

Interesting to read about John Duncan. I feel how work is often overlooked. He has been overshadowed by The Glasgow Boys and the Scottish Colourists, as has been Phoebe Traquair, another notable Scottish artist. I’ve always been much interested in Symbolist art. I have a fine book, ‘The Paintings of John Duncan, A Scottish Symbolist’ by John Kemplay, Pomegranate Artbooks, San Francisco, 1994, which gives a fine account of the artist and his work.

Thanks, Andy, for the book info. As a Scot from Clydebank, I have a good library of books on Scotland and Scottish art. I’ll hunt this one up.

Thanks, John for the inspiring blog, as always.

Andy: Thanks for the info, I’m pleased to hear there’s a book about Duncan. Makes sense that’s it’s Pomegranate, they like artists of his generation, and they do a lot to keep Harry Clarke’s work circulating.

Bernadette, I’ve a pretty good library myself not only on Scotland and Scottish art but much wider (as I’m sure your is too). I was interested to see a comment from a Bankie as I’m a Son of the Rock myself but many of my pals were Bankies as is the lady wife. John’s blog is an absolute must – I’ve discovered so much there.

An excellent blog post on a neglected Caledonian master of the otherworldly. Whilst we are on Scottish artists, are you familiar with the work of Norman Shaw? His art is indebted to the topics that interest us, and I like how he mingles Highland faery lore with wyrd fiction. Here is his site: https://www.normanshaw.land/

Thanks, Liam, Norman Shaw was news to me. I’m impressed that he maintains an abstract quality; many artists taking a similar approach wouldn’t be able to resist turning those lines into faces and figures.