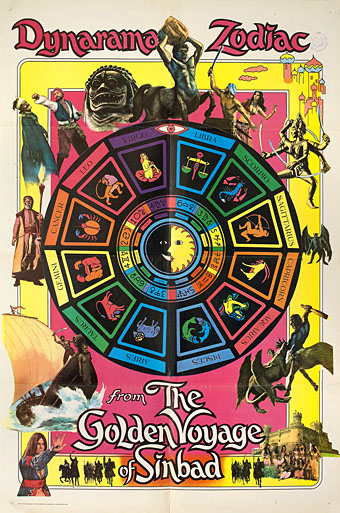

It was the 1970s: promoting Sinbad with a Zodiac poster for the blacklight brigade.

Last month I took advantage of the recent Indicator sale to buy blu-rays of a couple of favourite Ray Harryhausen films, together with Indicator’s reissued box of the three Harryhausen Sinbad features: The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973), and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977). I’m very familiar with these films but hadn’t seen them for many years. Watching them again made me realise for the first time what perfect examples they are of sword-and-sorcery cinema even though you never see them classed as such. I’ve been reading sword-and-sorcery fiction for almost as long as I’ve been watching Ray Harryhausen films but this rather obvious insight hadn’t occurred to me before, no doubt because I’d always regarded the Sinbad cycle as Arabian Nights fantasies in the manner of The Thief of Bagdad. The 1940 version of the latter happened to be a Harryhausen favourite which prompted his decision to film an Arabian adventure following his monster-on-the-rampage pictures of the 1950s. He subsequently asked The Thief of Bagdad‘s composer, Miklós Rózsa, to score The Golden Voyage when Bernard Herrmann was unable to do so.

Sokurah (Torin Thatcher) with a shrunken Princess Parisa (Kathryn Grant).

The 7th Voyage is at least based on the original Sinbad tales but the second and third films have little to do with The Arabian Nights beyond Sinbad’s persona and a handful of cultural references. If you swapped the Arabian names for invented ones then you’d be even closer to the stories of Clark Ashton Smith and his colleagues at Weird Tales than the films already are. Smith’s sorcery-infused fiction is the key here even though his stories are light on sword-play. The sight of a shaven-headed Torin Thatcher as Sokurah, the duplicitous magician in The 7th Voyage, was so strongly reminiscent of one of Smith’s many sorcerers—he even looks a little like Virgil Finlay’s depiction of Dwerulas from The Garden of Adompha—that I couldn’t help but watch the films this time as though they were adaptations of Smith’s fantasies. In The 7th Voyage the similarity is most evident in the scene where Sokurah demonstrates his powers to the caliph by temporarily turning a handmaiden into a serpent-woman, and the later scenes in Sokurah’s underground fortress. Smith and his cohorts in the pulp magazines were of course refashioning elements from The Arabian Nights and from other legends so none of this should be surprising. The 7th Voyage may take some of its scenes from The Arabian Nights but the story establishes the template which the sequels follow, with Sinbad pitted against a magic-wielding adversary.

Yes, Lemuria. Martin Shaw, John Phillip Law and Douglas Wilmer.

The Golden Voyage is the film where Harryhausen moves firmly into Weird Tales territory. This one also has the best cast of the three, with John Phillip Law as Sinbad, together with Martin Shaw, Caroline Monroe, Douglas Wilmer, and, best of all, Tom Baker as the sinister Baphomet-invoking magician, Koura. Screenwriter Brian Clemens had been working in TV for many years, notably as writer and producer of The Avengers, and was very adept at crafting stories replete with incidental detail. His script is filled with inventive touches: the sorcerer who visibly ages each time he calls upon the forces of darkness; the vizier who hides his ruined face behind a golden mask; the mystery woman with an eye tattooed in the palm of her hand; the golden tablets which Sinbad pieces together; the shadow-chart which the tablets reveal. There’s also a mention of hashish which isn’t something you expect in a film aimed at a very young audience.

Koura (Tom Baker) with his own Zodiac poster in the centre of which sits a pre-Eliphas Levi Baphomet.

One of the reasons I’ve always favoured this film over the first one is that The Golden Voyage is the only feature film to have Lemuria as its destination. The lost continent gained much of its exotic charge from its supposed location in the India Ocean, midway between Africa and India, even before it was co-opted by Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophists for whom all the lost continents were repositories of ancient wisdom. As with Atlantis, it didn’t take long for fiction writers to discard the mystical theorising and adopt the place for their own ends. The pulp magazines are littered with references to Lemuria. Robert E Howard refers to it in his Kull stories, and it was brought into the Cthulhu Mythos when HP Lovecraft names it as a temporary home for the Shining Trapezohedron in The Haunter of the Dark. Clark Ashton Smith wrote a short poem with the title In Lemuria, although few people would have read this in his Ebony and Crystal collection, a book with a limited run of 500 copies. Harryhausen and Clemens’ Lemuria is an island remnant of the sunken continent where Sinbad’s voyagers find an Oracle that speaks in verse (an uncredited Robert Shaw), an isolated tribe, more of Harryhausen’s battling beasts and a Fountain of Destiny. The island is also littered with mismatched architecture and iconography: Buddhist, Hindu, Cambodian, even Stonehenge-like trilithons. Much as I’d like to imagine Harryhausen and co. borrowing from Weird Tales by choosing Lemuria as their location the real reason was one of contingency; the island only became the voyagers’ destination after plans for Sinbad in India fell through. The Indian decor is a holdover from this, as is the film’s major animated sequence in which Koura brings to life a statue of Kali that sprouts swords from its six arms.

Koura and Kali. Tom Baker’s character was based on Jaffar, the evil vizier played by Conrad Veidt in the 1940 version of The Thief of Bagdad.

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger takes us to yet another lost world favoured by the Theosophists, Hyperborea, and this time the connection with Clark Ashton Smith is unavoidable when the same place is a setting for a whole cycle of Smith’s stories. The film is the weakest of the three, with Patrick Wayne as a duff Sinbad, and too much unconvincing blue-screen work. But Sinbad’s voyagers compensate for Wayne’s deficiencies, especially Patrick Troughton as Melanthius, the proto-scientist who guides the ship to the lost kingdom. The sorcerer this time is a woman, Zenobia (Margaret Whiting), a scheming stepmother with occult powers and a bronze ship powered by a minotaur automaton. This is a rare Harryhausen film where the animated creatures don’t all go on the rampage as soon as they appear; the troglodyte giant even helps open a pair of massive gates. The travellers also reach the ruins of Petra before Indiana Jones although this whole sequence is spoiled by repeated cutting to blue-screen close-ups. From The 7th Voyage on, the Harryhausen fantasies supplemented their moderate budgets with location filming around the Mediterranean, especially southern Spain where the Moorish architecture stands for various Arabian kingdoms.

Hyperborea and an Arctic pyramid.

The booklet notes in the Indicator box include a short discussion of what would have been a fourth feature, Sinbad Goes to Mars. This sounds like an unlikely concept (and Harryhausen and co. were unable to resolve their script problems) but John Carter is little more than a Sinbad-like adventurer leaping around the Red Planet. If the film had been made it would also have maintained the loose connection to Clark Ashton Smith who set a number of his stories on Mars. Despite this being proposed post-Star Wars the studios weren’t interested. Clash of the Titans replaced the project, and ended up being Harryhausen’s final film.

Epic fantasy is no longer as untouchable as it used to be following the screen success of the Tolkien and George RR Martin franchises, but sword and sorcery remains mildly disreputable, however much Michael Chabon may declare his enthusiasm. I don’t mind this, many of my favourite things have been deemed disreputable at one time or another, and not every story is improved by the blundering attentions of Hollywood. When mass media is eager to exploit every available genre and sub-genre it’s good to know there are still some untouched regions; not quite lost continents but undeveloped islands. Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser may prowl the smoky lanes of Lankhmar undisturbed while we continue to watch films like these for the right “wrong” reasons.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Illustrating Zothique

• Zemania

• Ray Harryhausen, 1920–2013

• The Thief of Bagdad

Favorite bit from the third SINBAD (saw 1st run in the theatre backintheday)–some Finlayesque ghouls…

>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k_wnyIK41AY

Highly recommended by this viewer as well:

Harryhausen-influenced Jim Danforth effects in JACK THE GIANT KILLER (1962)–Seen on a double drive-in bill w/Bert Gordon’s THE MAGIC SWORD [same year]

Raised on & love this stuff!

Damn, I ought to have mentioned those ghouls, they are very Finlayesque. Eye of the Tiger is the only one I’ve seen at a cinema as well. I wanted to see The Golden Voyage when it was first released but missed it. I’ve definitely seen Jack the Giant Killer but a long time ago.

I could have asked Harryhausen about his literary influences when I met him at a small SF society meeting circa 1992 but it never crossed my mind. I was happy enough to shake his hand then let other people pester him. He seemed happy with the attention, probably because he’d been part of a similar group with Ray Bradbury in the 1940s.

I taped the Sinbad films onto VHS, along with Jason and the Argonauts and Clash of the Titans, and watched them all many times in my youth. Have been revisiting various sword & sorcery films recently and starting to read some of the classic stories. Must be something in the air… Really wish they had made Sinbad goes to Mars!

There’s currently an exhibition; “Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema”, at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. It runs until 20 February 2022.

Leigh: The booklet doesn’t say much about the Mars film, unfortunately. although it seemed to involve a Genie taking Sinbad to Mars rather than a spaceship. There’s also a drawing of Sinbad being attacked by bat-winged creatures that look rather like the demons in Gustave Doré’s Inferno.

Andy: Thanks! I’d be tempted to make a day trip to see that if it didn’t involve sitting on a virus-filled train for most of the day.

Has anyone seen Baahubali 1 & 2 2015/2017?- Indian cinema often goes where others fear to tread and this is the closest I’ve seen to filmmaking in the spirit of Sword and Sorcery/Ray Harryhausen in quite some time – a lavish and very long, but entrancing production … and Season 3’s release is just around the corner!

Thanks, I’d not heard of those. Something to go looking for. My knowledge of Indian cinema is very patchy. I used to watch a lot of Bollywood films on late night TV but they were invariably musicals.

Hong Kong cinema has many films that fit the S&S label, those that combine martial arts with stories of wizards and demons. Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain is one I watched many times in the 1980s. I wouldn’t mind seeing it again.