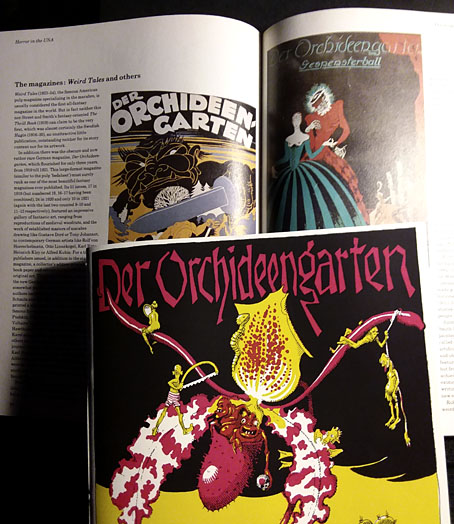

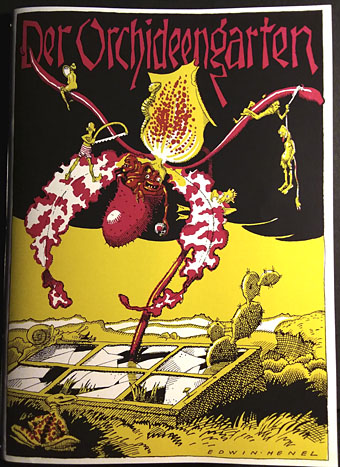

It’s a strange thing to compare the covers of Der Orchideengarten in Franz Rottensteiner’s The Fantasy Book (1978) with the facsimile of the first issue which has just been published by Zagava. For years the two covers and Rottensteiner’s laudatory description were all I knew of a magazine that nobody else seemed to write about. As with all such enigmas, this made the magazine all the more intriguing. Der Orchideengarten was short-lived, running from 1919 to 1921, and German, which no doubt did little to aid its post-war reputation. Whatever reputation it may have had was quickly eclipsed by Weird Tales and a host of other Anglophone publications some of whose creations still dominate the fantasy landscape today. One of the many services Rottensteiner’s study provided was to treat fantasy as a genre with manifestations all over the world, not only in Britain and America.

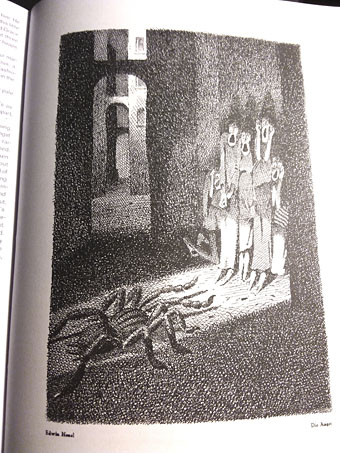

The visibility of Der Orchideengarten began to change in 2009 when Will at the now-defunct A Journey Round My Skull, having also had his curiosity piqued by Rottensteiner’s book, acquired a few copies of the magazine. I ran some of the interior illustrations here, the sight of which was genuinely revelatory since these weird and macabre drawings had been buried for 90 years. The situation changed again late last year when the entire run of the magazine was made available at the University of Heidelberg’s remarkable online archive.

What struck me in 2009—and what continues to strike me today—is the difference in tone between the illustrations, covers included, of Der Orchideengarten with its later Anglophone counterparts, especially Weird Tales. The latter presented itself very much in the pulp tradition, and many of the illustrators of the early issues were just as happy working with adventure or detective titles as they were with fantasy or horror. The German artists are less illustrational and much more grotesque, closer at times to Expressionist painting than anything you’d find in an American magazine. I continue to wonder how fantasy as a genre might have developed if it had owed less to Britain’s ghost stories and America’s adventure idioms.

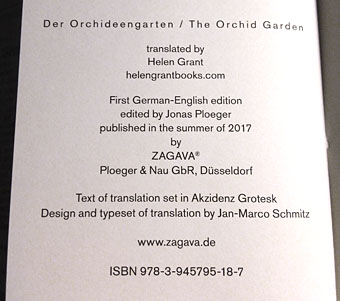

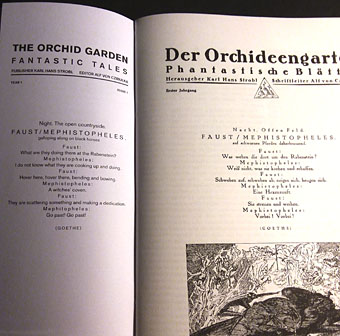

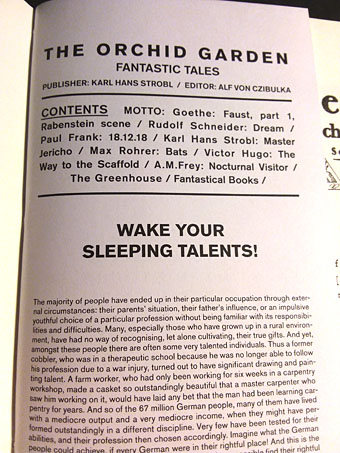

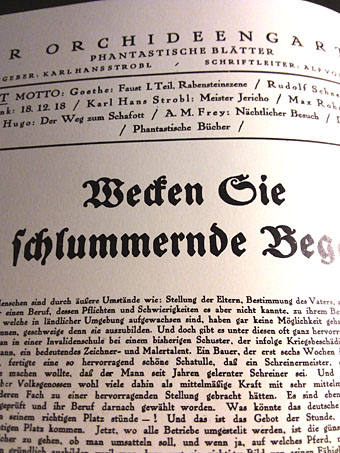

Any speculation is easier now we have this facsimile of the first issue which (as I mentioned in a weekend post) contains a translation into English by Helen Grant of the complete contents of the magazine. This has been cleverly achieved by interleaving narrower pages of translated text with the originals so the integrity of the magazine is maintained. The facsimile is a quality production with superb printing of all the illustrations and graphics. One of the ironies of our connected world is that contemporary magazines continue to be killed off while the easier accessibility of so much culture from the past makes resurrections like this one more likely.

Whether we see more facsimile issues will no doubt depend on the success of this first number which may be ordered here. A few more page samples follow.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Covers for Der Orchideengarten

• The art of Fritz Hegenbart, 1864–1943

• The art of Sergius Hruby, 1869–1943

• Der Orchideengarten illustrated

• Der Orchideengarten

John I ordered a copy as soon as you mentioned it back in October. It’s beautiful! Should also mention the pages are bound together with string. No staples to damage the pages. Zagava is a class publisher. I’m currently lusting after their newly published edition of the sketchbooks of Stanis?aw Szukalski.

There is a real sense of a “road not taken” here. F&SF in the US has never escaped really from the Pulp ghetto. Sure, Vonnegut and Dick and Lovecraft are allowed into the Library of America, but most people here will still think of Star Wars and Star Trek and Marvel Comics as completely representative.

I have a copy too. I discovered it a couple of years ago when looking for decadent art after reading Alfred Kubin’s The Other Side. Zagava have done a great job too. I’m impressed.

I first heard about Der Orchideengarten through Feuilleton. A wonderful artifact, happy to see it more available.