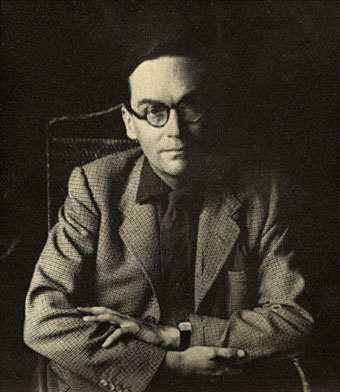

Monsieur Jullian as seen on the back cover of Dreamers of Decadence (1971).

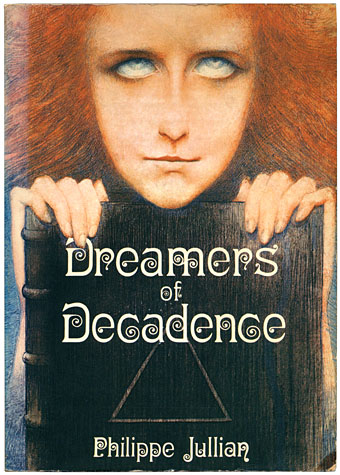

Here at last is the long-promised (and long!) piece about the life and work of Philippe Jullian (1919–1977), a French writer and illustrator who’s become something of a cult figure of mine in recent years. Why the fascination? First and foremost because at the end of the 1960s he wrote Esthètes et Magiciens, or Dreamers of Decadence as it’s known to English readers, a book which effectively launched the Symbolist art revival and which remains the best introduction to Symbolist art and the aesthetic hothouse that was the 1890s. If I had to choose five favourite books Dreamers of Decadence would always be on the list. This point of obsession, and Philip Core’s account of the writer, made me curious about the rest of Jullian’s career.

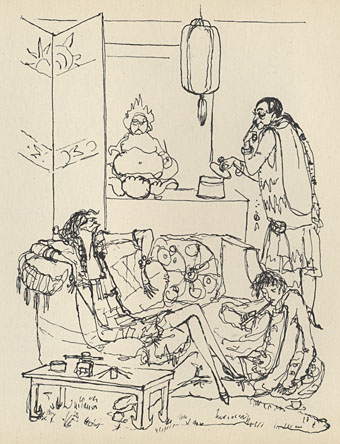

An illustration from Wilson & Jullian’s For Whom the Cloche Tolls (1953). “Tata has called these his Krafft-Ebbing (sic) pictures of his friend Kuno, whatever that means.”

Philip Core was friends with Philippe Jullian, and Core’s essential Camp: The Lie that Tells the Truth (1984) has Jullian as one of its dedicatees. It’s to Core’s appraisal that we have to turn for details of the man’s life. There is an autobiography, La Brocante (1975), but, like a number of other Jullian works, this doesn’t seem to have been translated and my French is dismally pauvre. Core’s piece begins:

Philippe Jullian, born to the intellectual family of Bordeaux Protestants which produced the well-known French historian, Camille Jullian, was a last and lasting example of pre-war camp. His career began as an artist in Paris with a reputation for drag-acts parodying English spinsters. Snobbery, a talent for sensitive daydreaming, and a consuming passion for antiques, obscure art and social history, made a very different figure out of the thin and dreamy young man. Jullian suffered terribly during the Second World War; he managed to survive by visiting some disapproving cousins dressed as a maiden aunt, whom they were happy to feed. However, he made a mark in the world of Violet Trefusis, Natalie Barney and Vita Sackville-West by illustrating their books with his wiry and delicate doodles; this led to a social connection in England, where he produced many book jackets and covers for Vogue throughout the 1950s.

Having only seen Jullian in his besuited and bespectacled guise it’s difficult to imagine him dragged up, but the cross-dressing interest is apparent in his humorous collaboration with Angus Wilson and in a later novel, Flight into Egypt. As for the wiry and delicate doodles, they’re very much of their time, in style often resembling a less-assured Ronald Searle. One early commission in 1945 was for the first of what would become a celebrated series of artist labels for Château Mouton Rothschild. Later cover illustrations included a run for Penguin Books some of which can be found at Flickr.

Philip Core continues the story:

Elegant in the austerely tweedy way the French imagine to be English, Jullian exploited his very considerable talents as a writer, producing a series of camp novels throughout the 1950s (Scraps, Milord) which deal frankly but amusingly with the vicissitudes of handsome young men and face-lifted ladies, grey-haired antique dealers and criminals. One of the first to reconsider Symbolist painting, Jullian reached an enormous public in the 1960s with his gorgeous book, Dreamers of Decadence – where an encyclopaedic knowledge of the genre and its accompanying literature helped to create the boom in fin de siècle revivalism among dealers and museums.

An acerbic wit accompanied this vast worldly success; always docile to duchesses, Jullian could easily remark to a hostess who offered him a chocolate and cream pudding called Nègre en chemise, “I prefer them without.” Less kindly, to a gay friend who objected to Jullian’s poodles accompanying them into a country food shop by saying “Think where their noses have been”, he could also retort “Yes, that’s what I think whenever I see you kiss your mother.”

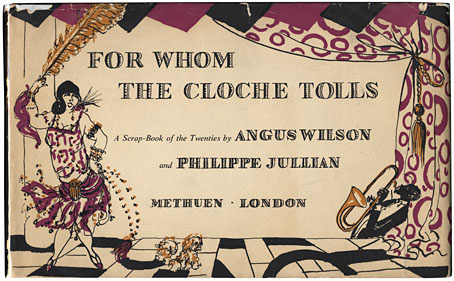

For Whom the Cloche Tolls: A Scrap-Book of the Twenties (1953).

Core’s account is running ahead, we’ll get to the Symbolism in a moment but first there’s For Whom the Cloche Tolls, a witty collaboration with the under-rated (and now sorely ignored) British writer Angus Wilson (1913–1991). This very camp confection appeared in 1953, a period when two gay men had to deliver their fripperies with some circumspection even though Wilson’s first novel, Hemlock and After (1952), was ahead of its time in looking honestly at gay life in Britain. For Whom the Cloche Tolls is presented in the manner of a scrap-book diary: Jullian’s illustrations are the “photos” while Wilson provides the voice of Maisie, an American widow recounting the adventures of herself and two adult children, Bridget (débutante daughter) and Tata (“witty aesthete” son), between the wars. The subtext is that Tata is charmingly homosexual, and much of the camp humour stems from the coded allusions to this which Wilson scatters throughout the story. Jullian illustrates every page, and many pictures look as though they were drawn first and had the caption added later. Owing to its age this is one of the more scarce Jullian titles although there is a later Penguin edition.

Incidentally, remember that story about Keith Richards snorting his father’s ashes with a line of coke? Here’s Angus Wilson in For Whom the Cloche Tolls:

What a curious story Tata told me. This couple (French apparently and very well born) took drugs (it was one of the tragedies of those times). A friend of theirs (a princess! French princesses, of course…) shared their tastes, but preferred cocaine to opium (such differences seem somehow only to make it all more degrading!) and one day found what she thought to be cocaine in a small china pot. It was only after she had been taking it for some weeks, that she learned from the maid that she was stealing the ashes of her hostess’s father! What a comment on the times!

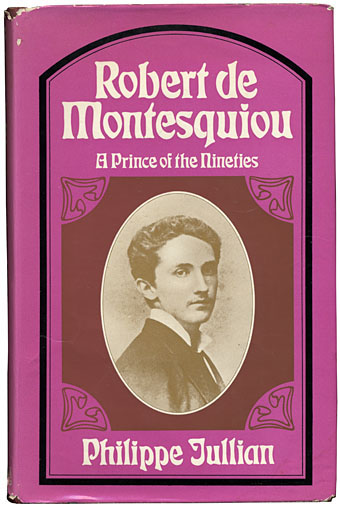

Un Prince 1900—Robert de Montesquiou (1965); Robert de Montesquiou: A Prince of the Nineties (1965), translated by John Haylock & Francis King. Cover design: Bernard Higton.

Jullian spent the 1950s and 1960s establishing himself as an illustrator, following the Wilson book with the aformentioned Penguin covers, and illustrated editions of Proust, Wilde and Dickens. His 1965 biography of aesthete Robert de Montesquiou (1855–1921) was the first substantial examination of the previously obscure life of a character who was nonetheless highly influential for a decade or two. Montesquiou’s precocious aestheticism, and accounts of the unique decor of his Parisian rooms, provided an inspiration for Huysmans which led to the writing of À rebours while his later appearance and impudent manner gave Marcel Proust the character of the Baron de Charlus. Jullian reveals that Montesquiou himself was less neurotic than Des Esseintes and far more reserved than Proust’s Uranian Baron. Jullian had been writing novels for a decade by this time but this was his first biography and compared to the later books it’s a little rambling, especially at the beginning where he has trouble keeping a grip on his material.

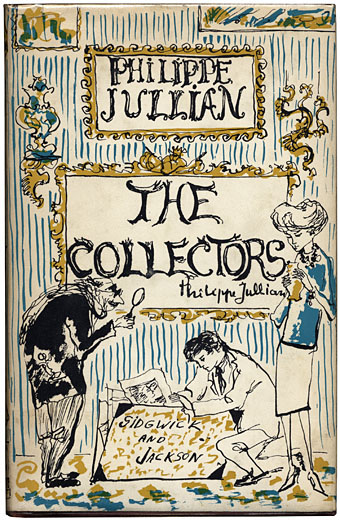

Les Collectioneurs (1966); The Collectors (1967), translated by Michael Callum, illustrated throughout by the author.

Adding this book to a collection of titles by its author ought to have caused the entire bookshelf to collapse into a singularity under the weight of the recursive significance… One of Jullian’s early non-fiction works was a dictionary of snobbery; The Collectors extends the theme, being a guide to all aspects of collecting, from the psychology of the collector to the different varieties of object one can collect. In the writing he often aspires to Wildean aphorism: “Numismatics is the philately of distinguished persons.” One chapter is of interest to this Jullian collector since it concerns the author’s own home in Senlis, France, and his collection of bric-a-brac. Despite his aesthetic interests I was surprised to read that his home wasn’t some fin de siècle oasis although he does mention having Alphonse Mucha posters in the bathroom. The book’s final chapter exemplifies a quality I enjoy about his writing: a British author of the period writing a dictionary of collecting would never include “Fetishes” and “Pornography” among the list. Jullian wasn’t prurient but he never avoided the sexual dimension in his discussions of art and literature.

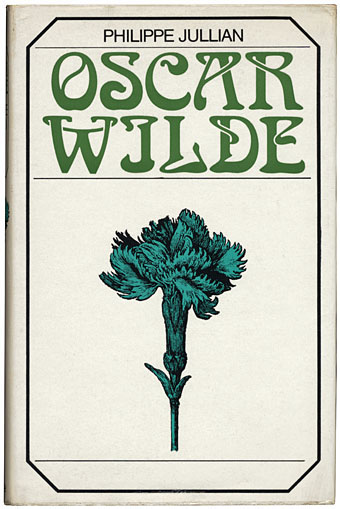

Oscar Wilde (1968); Oscar Wilde (1969), translated by Violet Wyndham. Cover design: Graham Bishop.

The second Jullian book I read was a paperback reprint of this beautiful volume which in its first edition comes with green boards and green endpapers printed with one of Wilde’s letters. Until the appearance of Richard Ellmann’s enormous 1987 biography this was one of the best lives of Wilde and it’s still a good introduction, less weighty than the Ellmann and often with a better insight into the artistic tenor of the period. Jullian had the advantage of talking to people who’d actually known Wilde as children or had parents who knew him. The translator was the daughter of Ada Leverson, Wilde’s ‘Sphinx’.

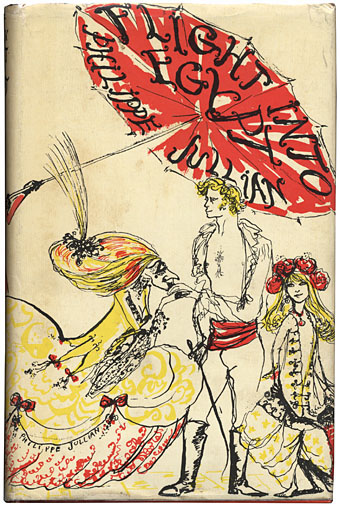

La Fuite en Egypte (1968); Flight into Egypt (1970), translated by John Haylock.

To date this is the only novel of Jullian’s that I’ve read. Rather than try and summarise this strange book it’s easier to borrow the précis from the dust jacket

Angus Wilson says of this book:

“The Flight into Egypt is a deceptively elegant book, for in it Mr Jullian makes a very serious and disturbing criticism of our times, which, however ambiguous and even distasteful its implications may he, must be met. Anyone who knows his previous work will expect him to offer this criticism with wit and serious frivolity; and he does. The Cairo drop-out who is the story’s Scheherazade gives to his novel what Sade failed to do through literary ineptitude.”What sex is concealed by these crinolines, their rustle competing with the palm trees by the side of the Red Sea? What famous faces are hidden behind these masks? Is it really Anastasia, can it be Maurice Sachs who run this scandalous boarding school where pretty children are trained in the art of pleasing? Can that be the Colonel Lawrence? Haven’t we met these arrogant and lascivious Marquises, these sinister and affected colonels somewhere before? Why are they here? To escape a Nazi past, or to surrender to pleasures which in Europe would land them behind bars? Do they dance better to the sound of the harpsichord or to the whip, these creatures who at midnight revels sometimes drown the nightingales? Are they ghosts or slaves?

Monsieur, the pet monkey of the so-called Grand-Duchess, is the last witness of this Firbankian apocalypse. Philippe Jullian, author of the much-admired lives of Robert de Montesquiou and Oscar Wilde, and painter of the exotic, finds him in the streets of Cairo. He follows his blind keeper into Turkish baths, into cafés, and into tombs, and elicits from him, as from a modern Scheherazade, the secrets of the Flight into Egypt. It could also he called All Aboard for Sodom. Is the tale he hears a fantasy, or is it, as the author tempts us to believe, true?

Author photo from Flight into Egypt (1970).

The occurrence there of a key Jullian word, “Sodom”, tips the wink that the précis is the author’s own. Mention of Firbank is apt although this book lacks the frivolity of the delightful Ronald. A Frenchman en vacances in Cairo encounters a blind European beggar whose description of wild adventures in the desert may or may not be the truth. The result is less like Firbank and more like one of Edward Whittemore‘s Middle Eastern fantasies but without the fantasy and, it should be said, without Whittemore’s humour. Like many tales of excess it turns out to be a distinctly moral piece. My copy is a UK edition with cover art by the author; the more common American edition replaced this with a rather tasteless design.

Esthètes et Magiciens (1969); Dreamers of Decadence (1971), translated by Robert Baldick. Cover: Portrait of Madame Stuart Merrill (1892) by Jean Delville.

The magnum opus. Alan Moore owns a copy of this book, as does Michael Moorcock. When RE/Search interviewed JG Ballard in the 1980s they took note of the books on his shelves and Jullian’s volume was mentioned in the published list. Dreamers of Decadence is dedicated to Professor Mario Praz, author of another classic work, The Romantic Agony (1933), and a book whose scope and erudition Jullian would have sought to emulate here, a thorough introduction to a period of art which had been buried for sixty years, as well as a splendid textual composition. Jullian takes as his starting point an unfinished Gustave Moreau painting, Les Chimères (1884), and uses the symbol of the Chimera as a guide through the many different aspects of literary and artistic Symbolism: the Legendary Chimera, the Mystical Chimera, the Macabre Chimera, the Erotic Chimera, and so on. He was fortunate to have this labour of love translated by Robert Baldick. I can’t resist highlighting this paragraph:

One of the greatest influences, that of Edgar Allan Poe, came from the United States, where Decadence would not set in until over a century after the poet’s death. Poe had an immense influence on Redon, for example, who made lithographs entitled Le Pèlerin d’un monde sublunaire (and here we can see the continuity of fantasy down to Lovecraft), La Cosmologie du poème ‘Eureka’, and Le Souffle qui conduit les êtres est aussi dans les spheres; many other fin de siècle figures saw the world lit by the cabbalistic star of Gérard de Nerval, Poe and the Victor Hugo of Ce que dit la bouche d’ombre: the Black Sun.

Jullian ends the book with an anthology of Symbolist themes that’s a feast in itself, a list of significant motifs and well-chosen quotations. All art books should be this good.

French Symbolist Painters (1972), exhibition catalogue.

French Symbolist Painters: Moreau, Puvis de Chavannes, Redon and their followers was the first major British Symbolist exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, London, and the Walker Gallery, Liverpool. Jullian was one of the organizers and he provided an introduction for the catalogue that successfully encapsulates a sprawling art movement in a few pages.

D’Annunzio (1971); D’Annunzio (1972), translated by Stephen Hardman.

Here your narrator abdicates his duty and has to admit that he’s yet to read this biography of dramatist, poet, aeronaut, minuscule seducer and proto-Fascist Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863–1938). This volume arrived when I’d just read the Robert de Montesquiou book and wasn’t in the mood for another lengthy life. D’Annunzio’s career connects to many points of interest for his biographer but I’d rather have seen a Jullian book about Ludwig II (who features in Dreamers of Decadence) or an English translation of his Jean Lorrain biography.

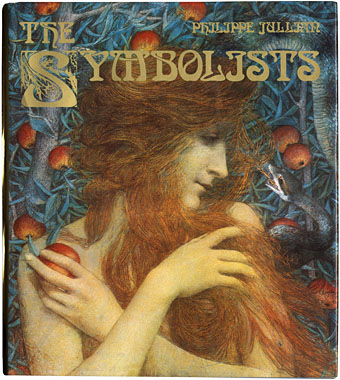

The Symbolists (1973), translated by Mary Anne Stevens. Cover: Eve (1896) by Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer.

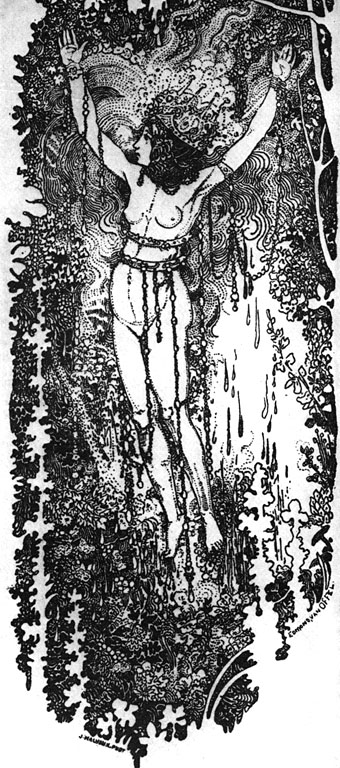

Dreamers of Decadence was published in paperback by Phaidon and the book’s success led to a series of commissions from the same publisher, beginning with this large-format volume which works well as a supplement to the earlier study. Many good colour reproductions and a few pictures I haven’t seen reproduced elsewhere including the following drawing.

Summer Rain (no date) by Edmond van Offel.

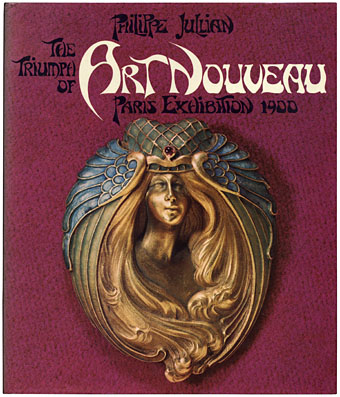

The Triumph of Art Nouveau (1974), translated by Stephen Hardman. Cover: pendant design by Samuel Bing.

A marvellous guide to the 1900 exposition which has been a regular feature here for the past two years. By 1974 the Art Nouveau revival was in full swing which explains the curious title. Jullian does however emphasise that Art Nouveau reached its peak as an avant garde movement during this year, and at the Paris exposition in particular where many of the national pavilions showed their own variations on the style. For a contemporary view of the events he borrows reminiscences from the famous—Jean Lorrain, Oscar Wilde—and the obscure, including a black gentleman, Gaston Bergeret, whose memoir (French language only), Journal d’un nègre à l’exposition de 1900, can be downloaded at the Internet Archive.

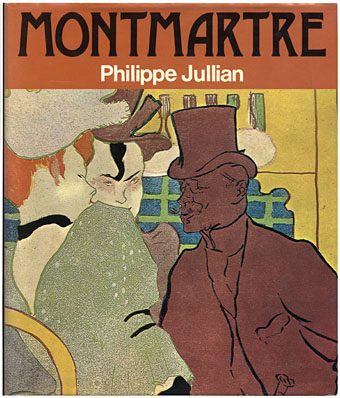

Montmartre (1977), translated by Anne Carter. Cover: The Englishman at the Moulin Rouge (1892) by Toulouse-Lautrec.

I’ve never understood the peculiar Anglophone obsession with Montmartre in general and the Moulin Rouge in particular, it always seems part of that repressed attitude which sees French sexuality as “naughty” whilst regarding the homegrown variety as “dirty”. English people who fixate on Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec are often semi-philistine in their tastes; they don’t know much about art but they know what they like, and what they like is cancan dancers and quaint pictures of women they’d never regard as prostitutes even when that’s what they are. Jullian’s history of Montmartre is a welcome tonic to all of this, stripping away the Hollywood clichés and showing us the evolution of the butte from an accumulation of hovels and windmills to an artist’s colony and the centre of Parisian nightlife. As thorough a guide as his earlier books and, typically, he doesn’t avoid the erotic dimension with three whole chapters devoted to the sexual life of the area: Mount Lesbos, Mount Cythera (straight prostitutes) and The Boulevards of Sodom (gay men and boy prostitutes who Jullian tells us were known as Jésuses).

There are other Jullian volumes I’ve yet to acquire, among them a biography of Violet Trefusis and a study of Orientalist painters for Phaidon. There are yet more untranslated works, including further biographies of Sarah Bernhardt and Jean Lorrain. The latter I’d especially love to read but it seems that I’ll have to brush up my French in order to do that. As for the author, he took his own life in 1977 at the age of 58. Philip Core has this to say on the matter:

Although Philippe Jullian’s suicide in 1977 was a bitter blow to his many friends, there was a camp element to his death which only he could have managed. In his autobiography, La Brocante, he not only announced that he would take his own life, but hoped his ashes would be auctioned, in a celadon pot from his motley but fascinating collection of bric-a-brac, to unsuspecting buyers at the Hôtel Drouot Paris’s great auction room.

Or failing that they could be snorted away by a group of dissolute aristocrats; I suspect that anecdote from For Whom the Cloche Tolls was one of Philippe’s after all.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

• The illustrators archive

• The Oscar Wilde archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Le Manoir a l’Envers

• The Art Nouveau dance goes on forever

• Teleny, Or the Reverse of the Medal

• Delville, Scriabin and Prometheus

• Ma Petite Ville

• Philip Core and George Quaintance

• The art of Giulio Aristide Sartorio, 1860–1932

I picked up ‘Dreamers of decadance’ years ago in a 2nd hand shop for the princely sum of £3.50, and it’s something I return to quite often.

I had no knowledge of the author apart from this book, and now I’m definately going to have to seek out some other works.

An excellent post. I actually bought a copy of French Symbolist Painters two days ago and am now tormented by the knowledge that all those incredible works were on display in my local art gallery (the Walker) while I had barely learned to read. Sigh.

Dave: That was a fortunate find. Exhibition catalogues are seldom reprinted so they get increasingly scarce as the years pass. If you go to Paris then the Gustave Moreau museum has many of the paintings that were on display, as well as Les Chimères.

For some reason this reminds me of Raymond Roussel

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GqrH9laEamI

http://www.themodernword.com/reviews/roussel_impressions.html

reasons probably include

Rich French intellectual who committed suicide

Jullian doesn’t have much more in common with Roussel aside from that. His fiction writing is quite conventional.

What a delicious post! Kudos!

John,

A wonderful article. My book collection boasts several of those titles you mention.

I also have the Scott Moncrieff version of Remembrance of Things Past.in Chatto & Windus paperbacks, which all have cover art by Jullian, and a hard cover edition of The Captive that has several plates. His Baron De Charlus is spot on.

Quite good, really enjoyed this post.

Your affection for Julllian is infectious. I have just purchased “Montmarte”, I’ve had his volume concerning Art Nouveau for years, thought it has been well loved, I was not aware of the author’s significance. If you love him, and Core loves him(“Camp” is an essential addition to any library) that I too must follow suit.

Thank you for adding to my shopping list.

take care, always a pleasure.

Leonard

His introduction to the first book of Baron De Meyer’s photographs is ravishingly evocative, and not to be missed. The volume itself can be picked up quite cheaply.

Hi Jimbo. Thanks, another one to look for!

Sad to hear he took his own life – a wonderful, witty and charming writer. Dreamers of Decadence is easily one of the key books in my life, id be a different person if i hadnt encountered it in the local library as a teenager.

A great post. Thanks John

That detail of his suicide seems so unlikely, doesn’t it? Ordinarily one might suspect an illness or depression but then there’s the comment from Philip Core saying he announced it in advance. I’d be tempted to say we may never know anything further but one thing that’s become apparent from making these posts is that people often arrive with further information. We’ll have to see whether that’s the case here.

Despite his achievements I believe he felt thwarted in life, as per Kenneth Williams, and was equally constrained. He seems to have measured himself against others. He writes The Flea (not translated) of visiting Roger Peyrefitte in his lavish apartment, and giggling at his pederastic haute knicknackery, such as a set of marble buttocks on a velvet cushion, and wishing that he had possessed such financial resources as he would have purchased a Bronzino or an original kouros instead. A sentence from his De Meyer essay I recall: ‘chic is endangered and panache is dead’. Well, not dead while dear Princess Michael lives amongst us.

That seems fair to me. People probably expect that someone who’d had so many books published would have felt he was doing okay, which by many standards he was. But achievement doesn’t prevent people from still being ambitious or feeling thwarted, however creative or successful they might be.

A great discovery!!

My late brother, the artist and aesthete Philip Core, was a great friend of Philippe Jullian. He worked as a researcher for him in the beginning of the 1970s when he (my brother that is) was still very young. He was deeply affected by Philippe’s death.

This review definitely wet my appetite for a good read – I’m going to look up Dreamers of Decadence this weekend. I’m a sucker for a well designed book cover too – never hurts in an sea of possibilities.

Thank you for this excellent presentation. I discovered Jullian today when I was lucky enough to buy at a second-hand bookshop his “Les styles” with a dedication by his hand (YES!!!) to Dina Doms, a Belgian journalist. What a gorgeous book. I must say I enjoyed the content of other pages of yours. My compliments!

Hi Natalia. It’s always good to hear that people appreciate a post. I wish more of Jullian’s titles were available in English.

His biography of Wilde remains my favourite. This is such a fabulous post and I thank you for it.

Thanks, Wilum, glad you enjoyed it.

can you kindly and urgently tell me if les styles and les collectionneurs is the same book? pls respond to cpetkanas@yahoo.com

Hi Christopher. I haven’t seen any of the French editions but those sound to me like different books.